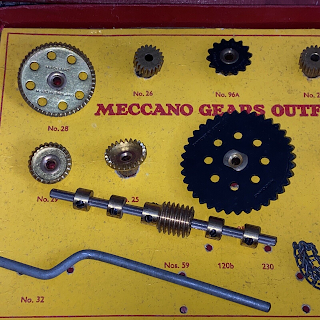

If you travel along Meanwood Road in Leeds you will pass the premises of Kingfisher (Lubrication) Ltd, a company that has been in business since the 19th century and which is mainly known for its precision made grease nipples. The Fisher family were the owners and in the 1950s their son Denys Fisher decided to go to his local university to study engineering. After leaving The University of Leeds Denys then joined the family firm, but he soon decided to set up his own company, Denys Fisher Engineering. By 1961 his company was supplying NATO with springs and precision components for its 20mm cannon and Denys Fisher had begun rethinking how to use his boyhood Meccano sets. In the early 1960s he developed drawing ideas by fitting pencils into the various holes in Meccano pieces, many of which were gear wheels, and seeing what sorts of shapes could be drawn.

Fisher began to realise that a combination of geared precision engineering and the geometric logic that lay behind the drawing of forms such as cardioids, could be combined to create drawing tools. As an engineer he was used to using drawing stencils when needing to make complex shapes and in the 1960s these were usually made in transparent plastic. A new fad had been around for a few years called 'nail art' and it relied on the development of geometric forms from straight lines. What this had done was to show the general public how beautiful pure geometric form could be and in a time that had a very positive view of everything scientific, geometry not only seemed beautiful, it seemed to offer a future far removed from the grim days of the second world war. Nail art brought an appreciation of maths and engineering into the living room. Simply by having one of these artworks on the wall, it was believed that children would see how beautiful geometry was and would want to be scientists and engineers when they grew up. You can imagine how a trained engineer like Fisher would have seen the potential of the circle if the straight line could be seen as such a powerful shaper of beautiful forms.

For instance a cardioid is formed by rolling a circle's path across the circumference of another circle, all the while keeping its radius the same. The cardioid is named after the Greek word for "heart" and I suspect it would have been one of the forms made by straight lines that Fisher looked at. The important fact was that its beauty could be appreciated by people who were not also engineers or scientists and he may well have seen a string art cardioid on someone's wall. However although it looks like a Spirograph image, it isn't.

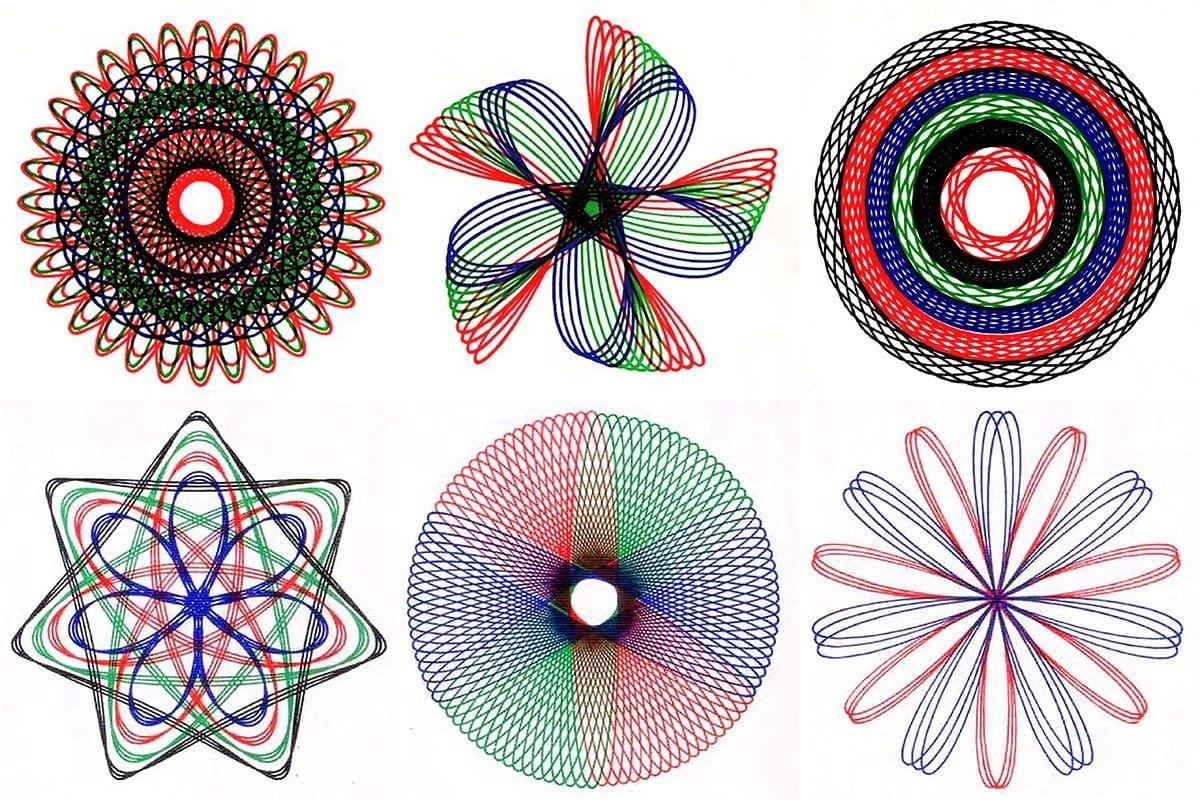

A Spirograph produces mathematical roulette curves of the type technically known as hypotrochoids and epitrochoids. A hypotrochoid is a roulette traced by a point attached to a circle of radius r rolling around the inside of a fixed circle of radius R.

An epitrochoid is a roulette traced by a point attached to a circle of radius r rolling around the outside of a fixed circle of radius R, where the point is at a distance d from the centre of the exterior circle.

For instance a cardioid is formed by rolling a circle's path across the circumference of another circle, all the while keeping its radius the same. The cardioid is named after the Greek word for "heart" and I suspect it would have been one of the forms made by straight lines that Fisher looked at. The important fact was that its beauty could be appreciated by people who were not also engineers or scientists and he may well have seen a string art cardioid on someone's wall. However although it looks like a Spirograph image, it isn't.

How to draw a cardioid

A cardioid

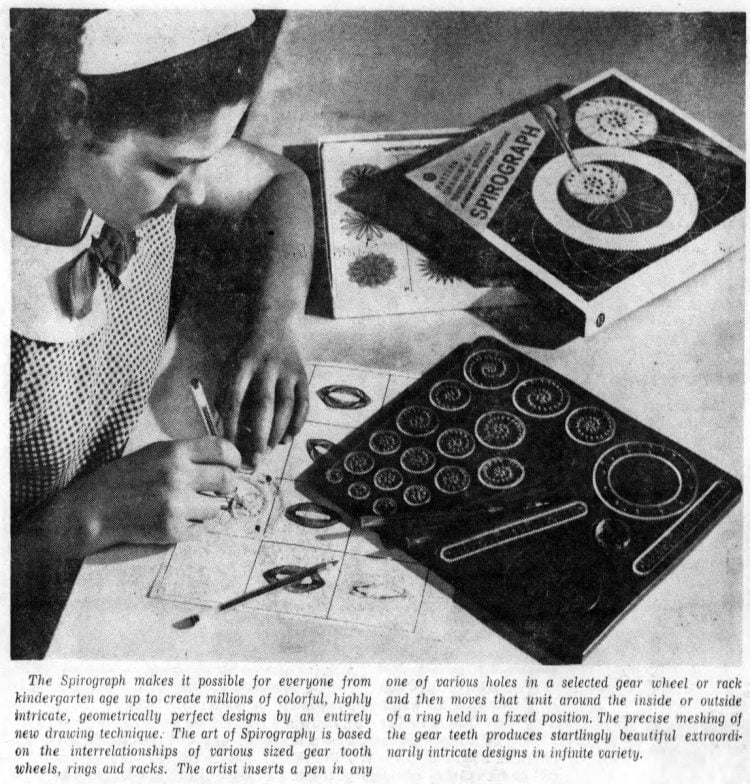

If you look at the image on the lid of a Spirograph box you can see how it works. One large geared wheel in the form of a flat circular band has a wheel moving around its inside, a hypotrochoid and a wheel rotating around its outside, an epitrochoid.

A hypotrochoid

The Spirograph as it was called, first went on sale in Schofield's department store in Leeds in 1965. A year later, Fisher licensed Spirograph in the USA and in 1967 Spirograph was chosen as the UK Toy of the Year.

Nothing escapes politics. The UK Government has for a while now been advocating STEM (Science Technology Engineering Maths) as the focus for the school curriculum and people in the arts who are worried about the one sidedness of this approach, have been trying to get the Government to also think of STEAM (Science Technology Engineering Art Maths). The Spirograph and its more recent competitors such as the Hypnograph have therefore had a revival. The blurb for the Hypnograph states this: 'Unlike other drawing machines that have hard to understand ratios, the Hypnograph uses an easily understood set of gears. They are all based on factoring the turntable which has 60 teeth. 60 factors into 2 x 2 x 3 x 5. This lets you easily understand the greatest common factor in the set of gears. A 30 gear has a Greatest Common Factor of 30 with the 60 teeth on the turntable. This means that the 30 gear will produce a drawing with 2 curves (nodes). The instruction book provides a chart so you don’t have to do the math but there is also a good explanation of what’s going on with the gears. A couple teachers have told me that it was the best visual explanation of Greatest Common Factor that they had ever seen.'

Wild Gears is slightly bigger than Spirograph and is designed with an adult audience in mind. It takes a high level of dexterity and control to use these gears and a fair amount of setting up. The key issue is that all of these drawing machines stress the interrelationship between art and science and assume that beauty of form is both an aspect of art and is arrived at as a result of following geometric principles.

If we now move on and enter the art world the same ideas persist. Geometric principles now described by the artist users as 'forces of nature' but take away the paint and the mess and what you have is another visualisation of a certain type of geometrical or physical principle. In this case instead of using a Spirograph, if you want to make a beautiful drawing, fill a bag with fine sand or drippy paint, tie it to a long string, cut a small hole in the corner of the bag and set up a pendulum construction.

It has been hard to escape Damien Hirst's latest venture. He has collaborated with international art services company HENI to present his latest project, 'The Beautiful Paintings,' which blurs the lines between digital and physical art through the use of generative and machine learning algorithms. I quote, 'Based on the British artist’s iconic ‘Spin Paintings’ known for their energetic splashes of colour, ‘The Beautiful Paintings’ allows collectors to access an online dashboard where they can choose their combination of colours, styles, shapes, sizes, and mediums to create unique pieces as physical paintings, NFTs or both.'

So it looks as if we combine geometric logic with soft curves we have 'beauty'. A while ago I looked at the Bezier curve and its attraction for the car industry, again we had a certain type of 'beauty' based on soft curves and an underlying mathematical rightness. There is a sort of satisfaction in seeing a regular form developed, especially one that is complex and still bi-laterally symmetrical or in other ways expressive of geometric order. Could it be that we recognise something of ourselves in these forms? Soft curves could easily be used to define biological entities like ourselves, but also plants and flowing forms such as water.

The harmony of these forms has been associated with the all pervading presence of God in everything and is therefore deeply embedded into Islamic culture.

The artist Jim Gregory has even produced a Mandala Colouring Book. He states that he values the symmetry involved, and considers the experience of colouring them in, to be a spiritual and meditative one.

It was Picasso that said "It took me four years to paint like Raphael, but a lifetime to paint like a child." In this case it takes a simple purchase on Amazon to allow a child to paint like Damien Hirst. But these mandala shaped images will always fascinate us, they hold our attention perhaps because the source of all life is spherical and within its contours there are constantly changing and reforging rhythms of energies of unimaginable power and complexity.

See also

The US advertising blurb stated that 'No artistic talent is needed to create handsome decorations in black and white or colours — ranging from simple figures to fantastically intricate patterns.'

The blurb went on to state, 'Professionals have actually used the Spirograph to design fabrics for dresses, patterns for plates, and ornaments used in printing. But for most people, it will be enough to enjoy the fun of making the designs that the set produces in fascinating, endless variety.'

So you had a product that covered both the art and design worlds and you didn't need any talent, but it was also, 'Fun for math buffs, too. You needn’t have a bent for math to enjoy the Spirograph — but if you have, it will fascinate you all the more.' This device seemed to straddle both art and science and as it was aimed at children, it could be seen to educate them in both art appreciation and science awareness at the same time.

The Spirograph toy was in fact a new version of an old idea. Precision machines called rose engines had long been used to engrave ornamental designs for paper money and if you have any, (I realise this is becoming a rarity) you might want to take a close look at it and you will probably find that it still has engraved into its surface the patterned decoration produced by a rose engine lathe, which is technically called a guilloché.

The blurb went on to state, 'Professionals have actually used the Spirograph to design fabrics for dresses, patterns for plates, and ornaments used in printing. But for most people, it will be enough to enjoy the fun of making the designs that the set produces in fascinating, endless variety.'

So you had a product that covered both the art and design worlds and you didn't need any talent, but it was also, 'Fun for math buffs, too. You needn’t have a bent for math to enjoy the Spirograph — but if you have, it will fascinate you all the more.' This device seemed to straddle both art and science and as it was aimed at children, it could be seen to educate them in both art appreciation and science awareness at the same time.

The Spirograph toy was in fact a new version of an old idea. Precision machines called rose engines had long been used to engrave ornamental designs for paper money and if you have any, (I realise this is becoming a rarity) you might want to take a close look at it and you will probably find that it still has engraved into its surface the patterned decoration produced by a rose engine lathe, which is technically called a guilloché.

Guilloché detail from a bank note

Nothing escapes politics. The UK Government has for a while now been advocating STEM (Science Technology Engineering Maths) as the focus for the school curriculum and people in the arts who are worried about the one sidedness of this approach, have been trying to get the Government to also think of STEAM (Science Technology Engineering Art Maths). The Spirograph and its more recent competitors such as the Hypnograph have therefore had a revival. The blurb for the Hypnograph states this: 'Unlike other drawing machines that have hard to understand ratios, the Hypnograph uses an easily understood set of gears. They are all based on factoring the turntable which has 60 teeth. 60 factors into 2 x 2 x 3 x 5. This lets you easily understand the greatest common factor in the set of gears. A 30 gear has a Greatest Common Factor of 30 with the 60 teeth on the turntable. This means that the 30 gear will produce a drawing with 2 curves (nodes). The instruction book provides a chart so you don’t have to do the math but there is also a good explanation of what’s going on with the gears. A couple teachers have told me that it was the best visual explanation of Greatest Common Factor that they had ever seen.'

Wild Gears is slightly bigger than Spirograph and is designed with an adult audience in mind. It takes a high level of dexterity and control to use these gears and a fair amount of setting up. The key issue is that all of these drawing machines stress the interrelationship between art and science and assume that beauty of form is both an aspect of art and is arrived at as a result of following geometric principles.

Tom Shannon

If we now move on and enter the art world the same ideas persist. Geometric principles now described by the artist users as 'forces of nature' but take away the paint and the mess and what you have is another visualisation of a certain type of geometrical or physical principle. In this case instead of using a Spirograph, if you want to make a beautiful drawing, fill a bag with fine sand or drippy paint, tie it to a long string, cut a small hole in the corner of the bag and set up a pendulum construction.

Joe Kotas

Joe Kotas

Artists like Tom Shannon and Joe Kotas have linked their more painterly approaches to pendulum type drawing machines and because of the perfection of form which emerges if you use a pendulum drawing machine, they have made 'beautiful' art. Do we have to remind ourselves of the 1960s advertising blurb, 'No artistic talent is needed to create handsome decorations in black and white or colours — ranging from simple figures to fantastically intricate patterns.'? Both Shannon and Kotas would state that the reason their work is so special is that they do have artistic talent. But it is perhaps Damien Hirst that has taken this type of idea on to its logical conclusion.

A work generated by The Beautiful Paintings by Damien Hirst

It has been hard to escape Damien Hirst's latest venture. He has collaborated with international art services company HENI to present his latest project, 'The Beautiful Paintings,' which blurs the lines between digital and physical art through the use of generative and machine learning algorithms. I quote, 'Based on the British artist’s iconic ‘Spin Paintings’ known for their energetic splashes of colour, ‘The Beautiful Paintings’ allows collectors to access an online dashboard where they can choose their combination of colours, styles, shapes, sizes, and mediums to create unique pieces as physical paintings, NFTs or both.'

Damien Hirst and a Beautiful Painting

Damien was always a smart cookie and he knows a winner when he sees one. I suspect like Denys Fisher realising that if you let a biro follow the logic of a moving point within spinning gears, Damien realised that if you put paint on a spinning flat surface something interesting will happen that follows natural laws. People like to see the result of a process where the final result reveals something about an underlying logic or law of nature, and often refer to that 'like' as 'beautiful'. But it is also no coincidence that all of these forms are based on circular movements.

Back in 2013, an exhibition in Washington, D.C., claimed that humans have an affinity for curves. The exhibition was based on the work of scientists who had created ten sets of images, each set included 25 shapes, which were all variations on a laser scan of a sculpture by Jean Arp. Upon entering the exhibition, visitors put on a pair of 3D glasses and then, for each image set, noted their “most preferred” and “least preferred” shape. The neuroscientists then reviewed the museum-goers’ responses in conjunction with fMRI scans taken on lab study participants looking at the very same images. The scientists found that visitors liked shapes with gentle curves as opposed to sharp points and the magnetic brain imaging scans of the lab participants backed up the hypothesis.

For thousands of years artists have produced either geometric patterns or used geometry as an underpinning design principle.

Islamic decorative pattern

The harmony of these forms has been associated with the all pervading presence of God in everything and is therefore deeply embedded into Islamic culture.

Mehandi Mandala designs

The artist Jim Gregory has even produced a Mandala Colouring Book. He states that he values the symmetry involved, and considers the experience of colouring them in, to be a spiritual and meditative one.

There does seem to be something going on here and the various approaches to what could be seen as very similar end results, suggests that an underlying meme is at work. I'm very interested in ways of thinking or ideas that become popular and therefore belong to popular culture and which also seem to pervade 'high art' or religious cultures. They can tend to be dismissed as kitsch, but the fact that they seem to rise up in so many different contexts, makes them for myself, powerful inter-cultural forms of communication.

What is also interesting though is how certain artists and engineers have tried to appropriate something that seems to be universal.

The spin art toys above are no different to Damien Hirst's spin paintings, except of course his are much bigger, on canvas and stretched onto frames. More importantly he would like us to believe that his ability to pour paint is more attuned to his artistic sensibility, and that his spin paintings are better than the ones made by various children over the years.

What was a child's toy, is also perhaps a reminder of deep hidden laws of form that pervade the universe.

Drawing together science and myth

The biro (Without the introduction of the biro into everyday use the Spirograph would not have taken off as it did. The roller ball technology of a biro enables it to move equally smoothly in any direction.

The biro (Without the introduction of the biro into everyday use the Spirograph would not have taken off as it did. The roller ball technology of a biro enables it to move equally smoothly in any direction.

No comments:

Post a Comment