There are moments in life when time and space seem to lose their hold on you. For example when I was knocked down by a car when crossing a road and everything was happening at the same time, a sort of clumping of experience in a way very different to 'normality'. Thinking about the experience from a distance I'm reminded of other people's attempts to describe the thing I might call an accelerated intuited moment. The term ‘sensuous aggregate’ is one taken from Husserl who used it to describe a ‘unified intuition’ (Farber, 2006) and is a term used to describe the various feelings and bodily knowledge that come to us through pre-cognitive thought. This ‘sensuous aggregate’ is something that I might also call a ‘feeling tone’ when describing an experience. In both 'Logical Investigations' and 'Ideas' Husserl argues that our perceptual consciousness is based in the “animation” or interpretation of sensory data or hyle. In philosophy, 'hyle' is a noun that means matter, especially matter in its original, unorganised state. In my case a road and a car in the rain at night. It can also refer to anything that receives form from outside itself, i.e. 'that which is formed'. Hyle when brought together with some form of representation, could I think be another type of sensuous aggregate. This is the intuitive or as Williford (2013, p. 1) puts it “in-the-flesh” aspect of perception, something we discover, rather than create, another possible bridge between consciousness and the experienced world. I would argue this is another aspect of what we also call our 'feeling tone'. It's the something that lies behind statements such as, "It's all going well", or "I'm anxious about something", "this is very exciting" or "I'm going to die". The general summation of my response to stimulus, determines my flight or fight response and is the overall judgement my embodied senses are making in response to what is happening out there. That judgement depends on the form I give to the perceptions I receive.

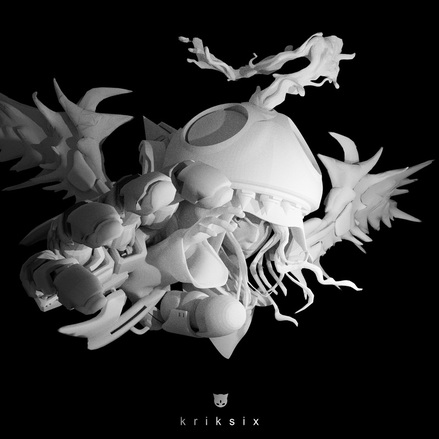

If so, another way to approach the images I have been making is to see them as diagrams of 'sensuous aggregates'.

Often more than one sense is activated at the same time when I have a feeling. So when I'm drawing I try to bring together into one representation more than one feeling tone. Perhaps a sense of cold shiver with a knotted stomach and a vision of an empty landscape on a misty day.

Deleuze and Guattari in response I presume to their reading of Husserl, stated that art relies on the creation of sensuous aggregates. (Rodowick in Furstenau, 2010, p. 31) So art itself could in some ways be pulled into this clump of aggregates. A clump that has now reminded me of 'the paradox of the heap', a philosophical puzzle that explores the vagueness of language and the difficulty of defining vague concepts. A heap is by definition an amorphous concept, and so is a sensuous aggregate. I know what I think I'm getting at but it might only be poetry that can save me. Heap, gravel, sand etc. out of which we build roads and buildings. But not that, something else.Aaltonen, Minna-Ella (2011) Touch, taste & devour: phenomenology of

film and the film experiencer in the cinema of sensations. MPhil(R) thesis. Obtained at: http://theses.gla.ac.uk/2666/01/2011aaltonenmphilr.pdf accessed on 14. 11. 11

Farber, M (2006) The foundation of phenomenology: Edmund Husserl and the quest for a rigorous science of philosophy London: AldineTransaction

Harvey G. (2015) The Handbook of Contemporary Animism London: Routledge

Williford, K. (2013) 'Husserl’s hyletic data and phenomenal consciousness', Phenom Cogn Sci.

1 DOI: 10.1007/s11097-013-9297-z.