Richard Long: A Line made by Walking

Continuing thoughts on material thinking.

As I was walking home the other day I took a well-trodden

route over Button Hill in order to save time. The path is well worn by

countless other feet taking the same short cut and it reminds me of Richard

Long’s walking pieces. But in this case the line of walking is simply made in

order to get from one place to another, there is no art intended. However it

can be understood in several ways. It tells a story of its own making, it is

evidence of how humans shape the world, but perhaps a shaping that is no

different to any other encounters between things. For instance there are paths just

off my route frequented by animals, these animal runs connect to places where they find food,

water or cover. These runs are much narrower than the tracks made by humans,

but are they any different? I can read them as signs of passage just as well as

I can read the fact that humans walked this way. There are secondary signs too.

In muddy places along my route I can spot both human boot prints and animal

tracks. These allow me to be more specific in my interpretations. Big boot prints

implying a heavy man passing, toe and heel prints implying someone running

rather than walking, paw prints suggesting that a dog passed this way. However

there are other material encounters with this landscape. As I work my way down

the hill I pass a shallow dip which acts as a funnel for rain water. Each time

it rains earth is washed down a slowly forming gulley and over the years I have

walked this way the gulley has gradually widened, making a clear drainage path.

People, animals and material forces are all testing themselves out against the

world and each leaves traces of actions taken. These events are about material

flow, the shape of the environment changing through elemental confrontations, wind and rain pushing elements against each other, a basic testing ground that includes the

humans walking in curved lines to avoid large trees or too steep inclines, animals making runs

through areas that give them good cover from predators, and water running down

the easiest route towards the stream below. These things are just what happens.

I’m getting older and as I make these notes with a

pencil I’m aware that my fingers are thickening with arthritis, the cartilage

that used to cushion my finger joints has worn away, my joints no longer move

smoothly and I’m slowing down. This physical change is inevitable and my body

is responding to years of wear and tear, continuously reshaping itself in response to its interaction

with the world. I am slowing down, until eventually I will reach the same speed

as a stone.

From the stone’s point of view I’m moving at a

very accelerated pace. The pebble that emerges from the path in front of me was

shaped millions of years ago on some far distant sea shore only now to emerge

back into daylight as the latest rain storm washes out the earth from around

it. Before it was a stone it was part of a rock face, itself composed of billions

of tiny compressed sea creatures, which themselves had processed other water dissolved

rocks in their making.

The stone is like myself

composed of a constantly changing material history. Over time the elements are

rearranged into new configurations, these configurations being responsive to

the environmental conditions that happen to be there during any particular time

period. Whether these elements are combined into organic or inorganic

relationships doesn’t matter, the line between the two being from the stone’s

point of view very blurred.

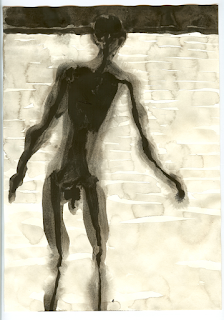

So what happens when the human being picks up the

stone and begins to draw with it? Looking at this from the stone’s point of

view it has simply entered into another abrasive encounter with the world. It

deposits some of its outer molecules onto the surface of another complex

material composite. However the human may consider these traces as being of

special significance, the traces may form the shape of an arrow for other

humans to follow or may be combined into some form of complex drawing. But it

could be argued that this is no different to the path made by walking. Some

people might look at the path and interpret it as a place where people run and

walk, some people might look at the marks and interpret them as an artistic

drawing and others as just marks. Consciousness allows the human to think about

the actions performed, but rarely about the whole situation, usually a human’s

awareness is focused on how the action will benefit humans.

Awareness is you could argue something that exists

on a sliding scale. Last week I heard a sharp crying noise outside and thought

it was a cat in some sort of confrontation with another feline. However when

I went outside to see, the noise was being emitted from a screaming frog that a cat had trapped in a corner of the porch. The frog was obviously in distress and

I rescued it and put it back in the pond, but it was a salutary reminder that

we are not the only life-form that has a high level of vital awareness.

We are descended from amphibians, which are the descendants

of fish, which are descended from...etc. all the way back to the moment when abiogenesis occurred. (The moment when life itself began) Every change in species was the

result of an environmental shift, but so too were the changes in material

formation. The atomic environment of suns shaping and creating elements by

first of all fusing hydrogen atoms into helium that then fuse to create beryllium, a process that

eventually will create every element

up to and including iron.

This material

awareness it should be hoped helps us rethink our belief in the special nature

of ourselves. It should help us think about our localised experiences as being

about direct physical contact with other elements, be these organic or inorganic

and to by conceptual projection begin to think of the global nature of existence

as being something that goes far beyond the human. Hopefully it allows us to

find universal truths in everyday experiences and to become more aware that new

possibilities of material formulations should not be the result of our forceful

control of nature but should be the result of finding a more autopoietic*

relationship with our environment. (*Autopoietic systems are

"structurally coupled" with their medium and embedded in a dynamic of

changes)

One way to think about drawing is as the trace of an action. This definition allows us to see drawing as an expanded field and gets us away from having to describe drawings as marks on paper. However it does raise some issues as to how drawing is also art, especially if expression is seen as a fundamental element.

Individual expression has

been a central issue for many artists, the idea of the signature work or

identifiable personal style is key to the way the art market works. The 20th

century saw an increasing focus on the inner life of humans. Psycho-analytical

theory was an important lens through which we were led to believe we could look

at our subconscious motivations and art appeared to be a way of articulating

this inner world. Surrealism and Expressionism in particular were rooted in

these beliefs and their offshoots including Abstract Expressionism relied on

sets of values that elevated the idea of the unique individual. We have been sold

the idea that we need to satisfy our inner needs and advertising has developed

a whole set of tools to ensure that we are constantly craving for things that

we feel will satisfy these desires. We are rarely encouraged to just be, to see

ourselves simply as part of the material flow of life; we are instead treated

as consumers. But as we consume the world we eat it up and if you eat more than

you need you also produce waste. Our waste has now reached the point that it

pollutes the whole earth, so perhaps it’s time to rethink the hubris of

personal expression.

There have been artists in

many cultures that didn’t sign their name to what they did, they operated more

like facilitators or people with making skills that helped that particular

society articulate certain ideas.

So how can a definition of

drawing as the leaving of material traces help anyone to do anything? Perhaps

the scratched mark that signalled the fact that someone went in a certain

direction gives us a clue. A tracker moving through unknown territory may make

marks on stones or trees so that others can follow, and the tracker has also

provided a way of finding a way back without getting lost. These marks are both

useful and can be used to communicate to others. We can though explore unknown territory

conceptually as well as physically, the things we do and make leaving traces

that can both guide others towards these concepts and make ourselves aware of

where we have been. It seems odd to argue that traces of our own actions allow

ourselves to become more aware of what we have done, but for many of us whilst

we are engaged with the flow of materials play, forms seem to emerge without

any conscious control.

Others as well as ourselves

can look back at the walk we have taken and see where we went, tracing our

steps back by looking at the flattened grass or muddy footprints. Because that

walk allowed us to get from A to B it will also allow others to do the same.

The first person to ever walk the route I took over Button Hill blazed a trail

that is still used every day by other people. So was that first walk across unknown

territory art? Not in the sense that we now understand it, but it would seem to

me that it could be useful to bring this idea back into the way we think about

what art is.

Various posts on this blog

have looked at approaches to communicating information through drawing;

mapping, tracing, technical drawing processes, drawing as performance, as

political statement, as document, as

materials investigation or as perceptual record, the best of the drawings used

as illustrations to these approaches I believe set out first of all to solve a

problem or to articulate an idea, and as the drawing attempts to do this, it evolves

in close relationship with the materials at hand and the ability of the maker

to sympathetically control these materials.

I am therefore suggesting

that self-expression should not be the central concern of the artist. By having

something to investigate that has purpose you can get lost both in the

investigation and in the making. The focus should be in the ‘now’ of discovery

and choosing appropriate methods and materials that can carry the ideas that

arrive from your investigations, as well as developing a feel for your chosen

materials or technologies, so that you can use them well.

Look at what is going on

around you and examine it closely, why are the things you see and experience

like they are? Try to develop a particular interest and research it in depth,

and make more and more trials and tests when trying out ways to articulate your

ideas, both to build up your skills and to put yourself into the situation

whereby you can discover what it is that you are doing. In the initial stages

of the research use as many approaches to drawing as possible.

Perhaps the most important

issue is to not worry about making art; that is something that can come much

later.

Joseph Beuys trained as a scientist, so was very aware of the physical properties of the world around him, later as an artist in both his teaching and in his actions he suggested that "art" might not ultimately constitute a specialised profession but, rather a heightened humanitarian attitude or way of conducting your life. The blurred territory between art and life, and the material nature of art thinking both suggest that we need to take more responsibility for a continuing re-evaluation of what it is to be an artist and perhaps in doing this will be able to embrace a much wider field of thinking. Today perhaps you need to draw and think like a geologist and tomorrow as a biologist but next week as an architectural technician.

Joseph Beuys

See also:

The imprint and the trace

Drawing as the trace of a touch

Drawing as material thinking