I recently hosted a celebratory life drawing session in honour of the achievements of an ex student of mine. He has for a while now been holding life drawing classes in Hull and has developed a core following of students, but is now moving on and another tutor is going to take over the classes. He wanted to mark the occasion in some way and so he invited me to teach a session in recognition of how a metaphorical baton is handed on from one artist educator to another. This reminded me of an another event I was invited to participate in back in 2017. The 'Fully Awake' Exhibition held in Glasgow at 'House for an Art Lover', was focused on the legacy of Fine Art teachers and I was chosen for my contributions to an understanding of the processes behind idea and image generation. In particular my contribution to opening out possibilities as to how stories can be translated into a visual simultaneity. In this exhibition I represented an older generation of art tutors and I was chosen by Steve Carrick, then Senior Lecturer in Fine Art at the University of Chester, as an important influence on his own practice, and he in turn chose one of his students as being someone who was themselves now carrying on the baton. The exhibition concept had been put together by Sean Kaye and Ian Hartshorne another two connections from my time working on the Foundation course at Leeds College of Art, Ian was a past student and Sean took over as head of the fine art strand, when I was pulled out of teaching to undertake management tasks, something that I spent a couple of very uncomfortable years doing.

In Hull, I felt I needed to do something that reflected how things had changed in relation to life drawing practices and that there was now much more awareness of the role of the model in the situation and I wanted to put on a session therefore that gave the model more agency and that brought the drawers into a three way dialogue, (drawers, tutor and model), that broke through the myth of life room objectivity.

The life model had decided to wear a thick black dressing gown made of a wooly material, which made him sweat. So I decided to use this as a starting point for the session. He was shaking his hands in some sort of attempt to cool himself down, so I asked him to just go through the moves he was making as cool down exercises and to now think of these actions as the focus for the session. He had a towel with him and he didn't know where to put it, so we agreed he might as well carry it over his shoulder, as he would normally do if he wasn't modeling. Whilst doing this I also engaged the drawers with their own body languages as they began setting up to draw. I asked them what they were thinking about and started to bring the model into the conversation. He told a story about how during one class he wished the session would end quickly because a nice looking woman was 'looking at him', which meant that he was starting to think that he might become aroused. He made it to the end of the session he said with relief and he had therefore decided that he must try to think of nothing when he was modelling in the future. His story reminded me of a life room conversation from back in the 1970s. I was as a young man hosting a life drawing session at the Swarthmore Adult Education Centre in Leeds, when the model came up to me and said, 'That man is looking at me', and I knew exactly what she meant. All the other drawers were engaged with the task in hand, which was trying to locate the figure in space, but this particular man was hardly drawing, he was looking at her. I then had the difficult job of informing him that it was better if he left the session and that I could tell that he wasn't capable of working in the required way, which was essential if students were going to progress into higher education. This was in fact an embroidered falsehood, only a few of the students in the group wanted to progress, but it worked and he left with a refund that came out of my own pocket. I wonder with hindsight if I could have handled the situation better? That story being a reminder to myself of how difficult life drawing sessions were and still are, in relation to the implied sexuality of the situation. I can't remember the number of times that some anonymous man I have met in a pub or waiting for a train, has grunted some guttural noise in response to the fact I had let them know I was an artist. In their mind all they could think of was that artists spend most of their time gazing at naked women. It's a sad indictment of our culture that this comic stereotype is still in place.

Back in the room booked out for the life drawing session, I began miming the various stances now taken by the drawers as they set up to draw. I suggested that one set of poses the model could take in the future could be based on these mimes. I was of course asking the students whether or not the life class could be used to reflect upon the situation itself?

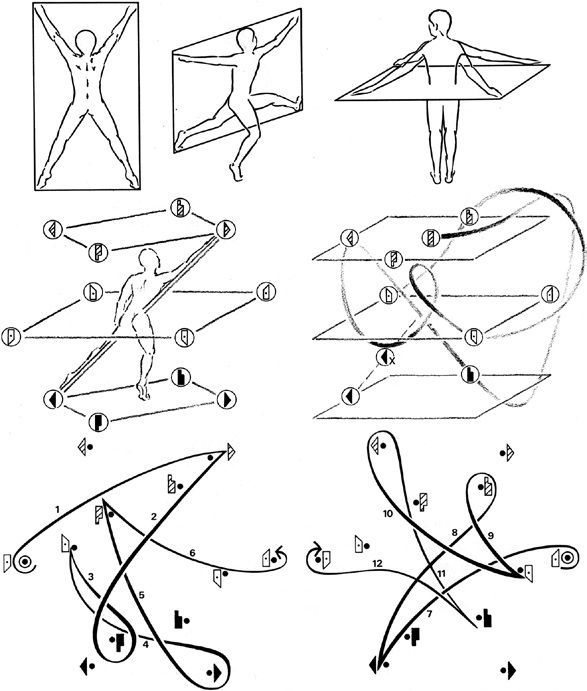

The next issue was to expand on an idea of figure drawing as some form of contact improvisation. I worked with the model to get him to undertake a range of classic poses, poses I would first take up and then he would if asked copy. As he moved, I moved an imaginary drawing implement with my hand, sometimes sweeping my arm in an arc and at other times twisting my wrist movements to make tiny hand turns. My drawing movements were echoing his body movements. If he held his arm out, I would extend mine, my imaginary drawing implement tracing an invisible line in the air as I moved. We then looked at how people were standing or sitting in relation to the situation and I asked how in their minds they inhabited their own bodies and whether they imaginatively could inhabit other people's bodies. Drawing in this case, could become a sort of 'inhabitation' of another's form. We also discussed mirroring, the way that we copy body movements of those we encounter, the classic being how we fold arms or cross legs in response to our perception of others doing the same.

Eventually we began drawing, and for the whole session I simply asked the model to continue with his cooling down routine, breaking every 15 minutes to ask questions of the various student approaches to their drawings. I took the approach of every picture tells a story. The drawings reflected the various abilities of those in the room in relation to measurement, control of medium etc. Several people still starting with drawing a head and finding as the drawing went on that they couldn't get the feet in. So lots of basic stuff to teach like how to measure, as we went on, but what these attempts did highlight were certain psychological implications in relation to how we see each other. I pointed out that in 'normal' conversation with another person we would not look at their feet and that we would concentrate on their face to check out whether or not we were in communication. However when one person in the room takes their clothes off, immediately the conversation is warped. Some broke their drawings down into flat areas, others developed centralised images, some were focused on mark others on tone. Each approach suggested a different narrative about relationships and how they could be visualised through drawing.

It felt that by the end of the session everyone was more aware of the possibilities for change in relation to the way that situations of this sort were constructed and that the key issue of how to make images of another human being was opened up anew for the students. In particular the man who was going to take over the life drawing sessions in the future took part and I would hope that what went on helped him to think through how he will host his sessions in the future.

We have been aware of these issues for some time and in particular Nina Kane unpicked many of the narratives surrounding life room practice when she worked for the Leeds College of Art Adult Education department during the time when I was its manager. I thought her work with the Leeds Art Gallery and its collection was exemplary and her reflections are still available. (A link to her work can be found at the end of this post.)

This was also a time (I think it was 2008) when the management at the college decided that life drawing would no longer be supported as a key component of the art curriculum and the life room was discontinued and the space put to other uses. The idea of continuing to fund a contested space was perhaps in the minds of a management driven by finance, as well as being faced with many mainly feminist voices calling for life drawing to be removed from the curriculum, difficult. Instead of using the situation to open out the issues as Nina had done, it was much easier just to drop what was a quite expensive activity, as both a tutor and a model had to be paid for, as well as changing facilities made available. There were also incoming health and safety regulations that highlighted potential dangers in having a nude person on the premises, regulations that demanded answers to hypothetical questions that made life too complicated for the average part-time tutor. So having been employed by a principal who insisted that I be able to draw from life and teach life drawing, I had now become one of the last people to ever undertake any life drawing within the institution.

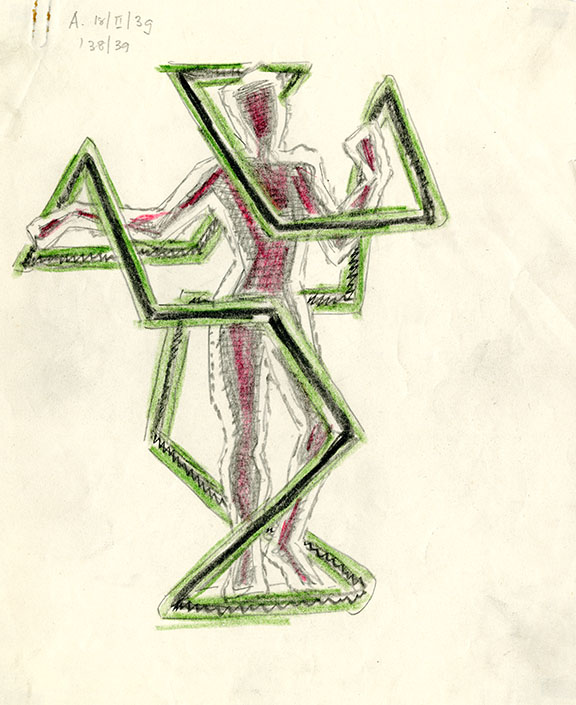

Things were so different when I started teaching in January 1975. Frank Lisle, the then principal, (in an earlier role teaching in Bradford he taught David Hockney to draw), employed three full-time models, Ann, Mavis and Rosalie. Life drawing was central to all the courses and I was employed, not just to teach printmaking but also to teach life drawing on Fridays to Foundation students. I'm again reminded of those times, because a film crew are in the university at the moment, developing a documentary about Lem Mierins' life. Lem was the inspiration for the well known comedian Leigh Francis' comic character Avid Merrion. Francis was taught by Lem as was the director behind this documentary, Phil Dean and as I'm one of the last members of staff that would have worked alongside Lem, I was interviewed. Lem is remembered for his language, a mixture of Latvian and English grammar, his iron will that he imposed on the life room and his very dapper appearance. He taught students how when drawing to reduce the model down to as few lines as possible. These lines had to be smoothly drawn and the model had to be placed perfectly on the page. I used to watch him draw, every line controlled, never a wobble and if it was Mavis, he had a model that had a shape that fitted perfectly into an imperial sized sheet of cartridge paper. (In 1975 metric paper sizes were introduced, but it took a few years for paper stocks to reflect this and we worked on imperial sized paper up until the later part of the 1970s.) He was an abstractionist and the life drawing studio was where he abstracted human beings down into formal essences. Then once your eyes were trained, you could apply this skill in other ways, such as in the precision kerning of the space between two letter forms. (This was in the days before computer typesetting) As you might guess we disagreed fundamentally on our relative approaches to drawing. I began with searching for space and then mass, he looked for flat pattern and formal organisation. Neither of us was at that time questioning why all three life models were women and it was accepted that whoever ran the life class, their philosophy would be the controlling factor. Things have though changed over the years; in Leeds in particular, the influence of Griselda Pollock's work was huge and as early as 1976/7, I remember Kate Russell, one of the Foundation staff, coming back from one of Griselda's sessions over at the University of Leeds totally fired up with the need to bring Feminist ideas into the course thinking.

Life classes are still being held in libraries and pubs and education institutions right across the city of Leeds, and I am aware that at times I feel the need to practice my ability to render the wonderfully complex form of the human body and that these types of classes offer an opportunity for me to do that. But I wish that more thought could be put into what the situation entails, as I believe that if that was done, eventually much more interesting drawings would emerge. I would hope that images that had far more to do with how we communicate through our bodies, would evolve out of a situation that was less about a myth of objectivity and more about the very subjective and emotional struggle we all have to communicate with each other.

See also:

Katja Heitmann and embodied memory

Kimon Nicolaides and the natural way to draw