When we draw freehand we make curves by using various parts of our body as if they were the arms of a compass. Drawn curves can be thought of as segments of a circle and the centre of each of these imaginary circles being the shoulder, the elbow or the wrist of the drawer, (or any other part of the body for that matter that you can use as a fulcrum or pivot). This determines the radius of the circle and therefore the type of curve that is being made; a situation obvious, but often forgotten.

Jasper Johns is an artist that once he has developed an image, pushes it through various print and drawing processes to test how far his image is a product of its media specificity. I find Johns' approach fascinating, and we rarely see such a control over image making. 'Diver' is one of his drawn images that isn't a drawing of a painting. The dark smudginess of the charcoal is more an intimation of death by drowning than perhaps a painted encaustic version would have been. In this image we can find various impressions of the artist, both his feet and hands appear, but above all we have an echo of a swimming stroke, the curve of the arms as they front crawl, being very similar to the curve made by the arms as they draw a circle, the drag of marks over the drawing's surface, echo the movements of hands struggling to swim up towards the sea's surface. Johns was thinking about the death by drowning of the poet Hart Crane, an event that happened some 30 years before he made the drawing, but a death that still resonated for Johns. He empathised with Crane's homosexuality, and he was interested in the way that Crane's poetry could sweep a reader along with swells of passion and the irrational language of love, something Johns was still struggling with in an early 1960s America that was yet to come to terms with homosexuality, something still treated as an unfortunate condition rather than a fact of life.

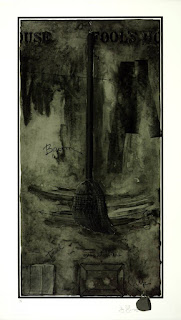

For Johns a brush could be a symbol for an artist. A paint brush is simply an arm extension with an artificial hand on the end. Fingers can be bristles, just as the arm can be the shaft of the brush. But brushes when they are brooms also sweep out the house, they can be central to a spring clean, as we brush away the cobwebs, we also clear our minds. Johns' interest in naming is also important, once an object is named or labeled, it has been "identified" as an thing and removed from its doing. The swing of the 'broom', leaves the trace of another arc or curve, something that is a sign of action rather than a fixed label. All of these issues could be regarded as tangental to the situation, a position that is of course a product of the geometry of curves, a tangent being a straight line that touches a curve at a single point. Each new subject or idea being tangential to the first subject; it touches it but then moves off in a different direction; which is sort of how I try to build the posts in this blog on drawing.

Look at the drawing by Rembrandt above, you can feel his wrist turning as he makes a variety of curves to build the image. He pulls his curves into and out of the spaces that they sit in. Bodies open themselves to his movements, curves never quite closing into circles, because he needs masses to merge into spaces. The child's hat provides a rotating fulcrum for the image, whilst the two flanking people are tied to the child by energy lines that open out into mass indicators. The speed of his visual notation is awesome, we feel the moment of capture in the drawing's swift curvature and Rembrandt's sensitivity to the punctum* of the situation in the way he establishes what is most important with total economy. This is the curve experienced in perceived life, far less conceptual than Johns, but a powerful thought non the less.

Vézelay was one of the first British artists to explore abstraction. In Curves and Circles she brings together cloudy abstract shapes, with elegant, twisting curves, curves that could almost be taken from an old manual on good handwriting that describes and traces the movement of the writer’s hand. The background resembles a cloudy sky or milky sea, as if the lines were floating in air or water, the curves move through this fluid space as would swimming snakes or nematodes, twisting lifeforms in a sea alongside other emerging micro organisms. These are curved lines as simple life forms, the curve as a basic building block for form.

Leonardo was fascinated by curves. His seated man is composed of curves, from the crossed legs to the folded arms, all is curved. Leonardo's interest in water and hair, is based on a similarity he finds between two ideas, the flow of a hair covered surface and the lines of water eddies. As he puts it:

See also:

No comments:

Post a Comment