Drawing excercises are a well honed tool for getting going when feeling stuck. They are also useful in that they point to various approaches to drawing that are fundamental. Therefore I shall occasionally post a few up as examples for anyone to try when stuck as to what to do.

These are a few suggested things to do which act as ice

breakers whilst you are thinking about what your subject matter will be and

what drawing processes you will use.

1. Developing

your sense of touch

Rubbings and textural mark-making

Materials

Materials for rubbings: Thin paper,

such as newsprint and photocopy paper or brass rubbing paper. Charcoal, Chinagraph pencil, soft

pencils i.e. 4B/5B, children’s wax crayons such as Crayola, blocks of brass rubbing wax.

Materials

for textural mark-making: As above plus a good varied range of artist’s

brushes, dip-in pens which are available in various nib sizes, black acrylic,

Indian ink, Quink ink, sponges both marine and synthetic, black oil pastels,

black and white chalks and pastels.

What to do

Take

rubbings of various surfaces, thin papers will let you achieve delicate marks

and thicker papers may be used for very rough surfaces. Each drawing material

will leave different traces so use a variety of these too. Try using different

hand pressures and changes in rubbing technique, such as loose open gestures,

then careful controlled ones.

The

next stage is to examine textured fabrics that you can’t take rubbings from.

Try to create marks that respond to the patterns or weaves of your fabrics,

Find ways to represent the differences between each fabric or surface examined.

Try and make rubbings of various objects, some will appear clearly, such as an outline of a pair of scissors but some will be almost impossible to recognise because they are too complicated.

Reference

Look at

the work of Ingrid Calame and read what she has to say about why she draws.

Try

using tracing paper laid over the rubbings to discover images or make connections between the various

surfaces you have produced.

Cut up and reassemble the various rubbings, in order to make images or abstract structures.

Drawing

your face or an object by touch.

Materials:

Use any of the materials suggested for rubbings and textual mark-making. You

might also need masking tape, black tapes and other non-traditional drawing

materials. For instance using a broken comb to make texture by scraping it

through an area of black boot polish. You might want to gesso your paper beforehand, so that you can scratch into it. Paper might be large roll size or small

units of paper that you add to.

Try to work on large sheets of paper, and make sure you have the

ability to extend these in any direction by cutting out extra rectangles and

adding them to the initial sheet of paper. Don’t try and check what your face looks like in a mirror beforehand. Before starting to actually draw, you can make a feeling test. Close your eyes and feel your head with the hand you do not use for

drawing. Starting at the back, think about how the hair gives an initial

textural set of information, then press harder to feel for the bone beneath.

One texture replaces another. Do not take your hand away in order to move it to

another area, keep it in contact with the head, moving slowly over your head’s

surface, once the back of the head is explored, the top of your head should be

investigated, then the front, then the sides, some areas being touched several

times as the hand makes its way between other sources of information. You are

encouraged to feel inside noses, mouths and ears, to think about how a pair of

glasses extends out from the surface of the head or how an earring may suddenly

change the textural world.

Then make a palette of marks, make tests and try outs using different

media whereby you are trying to make marks that approximate to touched

‘feelings’. Try scratching into the paper, especially if you have gessoed it.

Once you have made your tests, finally you can begin drawing. Try to forget what a head looks like (this is

impossible but the idea is that this drawing doesn’t need to rely on your

memory of what a head looks like), and to begin feeling again before drawing.

Again you are encouraged to start at the back of the head, remember that when

collecting ‘touch’ information, there is no back and front, just a continuous

surface and starting at the back might help you to get away from the 'look' of the head. As you start drawing you are to invent surface information as a trace

of passage. If you are feeling an ear, how does a mark change from hair, hair

over bone to the cave like entry for the finger, then how does the feeling tone

shift from open to closed surfaces? Fingers might trace their way across the

top of a head and down over the front, moving over one eye and missing another.

Alternatively a hand may be moving up from the neck, over the chin and then

move left once the mouth is met and go on towards an ear. Fingers may of course

explore the inside of the mouth and as this is just a continuous surface, the

information should continue to just spread over the paper as you draw. The implication is that your body is all one surface, and even though you can't follow the implications of touching the inside of the mouth down into the stomach, you might be able to suggest the idea that this surface has points or areas that change direction and become holes.

Questions such as the nature of up-ness and down-ness in a world without

sight could be explored. Is this drawing

now becoming more about distance positioning? One eye is perhaps ten thumb

lengths from the other if the feeling is done around the back of the head but

only a single thumb length, separated by a nose bridge the other way. How do

you know it’s the same eye that you are coming back to? If you were feeling

someone else’s head how would the information be encoded? You ‘know’ the fingers

have reached the nose if it is your own, but if you were feeling someone else’s head you might

perhaps mistake one area for another.

Once the first touching exercise is done another approach is to draw a continuous ‘felt line’; this is

done by drawing a line that stretches from the back to the front and to

the back and to the front again. Starting with perhaps the left ear, the

fingers feel over the front of the face (or back), to the right ear, around the

back to the left ear again and onwards to the right ear again. If there isn’t

enough room on the paper for the marks you can add an extension. Try and make

the texture visual, as these are not drawings that will be read by touch, they

will be looked at and the link between touch and sight will be what becomes

interesting.

Once the drawings are done, consider making relief images from them or embroidery or re make the drawings back into 3D shapes.

Drawing an object/objects

by touch

Get someone to place an object in a bag or box that you can put your non

drawing hand into. Don’t look to see what it is and don’t let them tell you

what it is. Then using touch alone draw the objects/objects, using everything

you have learnt from the drawing your face by touch exercise.

Your drawings should show a sensitive response to touch and contain a

range of interesting felt marks. You are making an abstract translation of how

your object feels, not a literal representation of how it looks. What is

important is the synchronised route of communication between both hands and the

transference of one sort of information (touch) into another (drawn marks).

Reference

Look at the work of Margarita Gluzberg and read what she has to say

about why she draws hair.

Make two sets of drawings and then try and use one set to remake the object as best you can, finally you are allowed to look at the object.

2.

Drawing

and Memory

There is always a gap between looking

and drawing, in that gap you forget things. This gap is though of vital

importance in the development of ideas related to visual importance and

conceptual weight. Gainsborough used to test his visual memory by setting up a

still-life in his basement and putting his drawing studio in his attic. He

would spend time looking and then run upstairs and draw until he could remember

no more. He hated climbing stairs so worked hard to develop his visual memory.

Here are two ways to approach this

issue.

Bridging

the memory gap

Using a drawing board, pencils and

cartridge paper position yourself in relation to your subject matter, (this can

be a still life, landscape, person etc. but if stuck the best object to draw is

a stool or chair sitting in space) so that you can only see your drawing paper

out of the corner of your eye. You should be able to see only your subject

clearly, not your drawing. Hold your pencil in a relaxed and comfortable way

between your forefinger and thumb of the hand you don’t draw with and position

yourself at arm’s length from the paper surface.

Without looking at the drawing and

keeping your arm extended at a comfortable full length, start to push and pull

the pencil around, trying to synchronise the lines you make with what you are

seeing.

Keep your pencil in contact with the

paper and move it continuously. (If you get tired take a rest, your shoulder

muscles will ache as the drawing progresses so do give yourself a rest). Work

slowly and keep to one continuous line. Twist and turn the pencil, sharpen it

to a chisel end, press lightly and hard. Try to produce an unpredictable,

awkwardly interesting line.

Make sure you don’t concern yourself

with the drawing. Concentrate on the looking. Draw until you can’t do it any

more; then finally look at what you have done. If you have to have a break,

don’t be tempted to look at what you did.

Check this out

Part 2

Repeat what you did for the first

drawing, this time using your drawing hand. You will need to reposition your

drawing board on the other side of your body, so that you can’t see the

drawing, as before only what you are drawing.

This way of drawing helps you get the

idea of drawing as a discovery, as a process that allows new things to happen

and it facilitates awareness. What you can hopefully do is develop a much better synchronised communication between the eyes and the hands.

Starting

to look, but only occasionally

Set up as before, however this time if

you are using an easel and drawing with your right hand, you may find it better

to look to the left side of your board. You need to be able to see in such a

way that only tiny head movements are needed to be able to see the subject and

the drawing. The time between looking and mark making needs to be as short as

possible.

Only glance at your drawing every 20

seconds or so to check that the drawing is in roughly the right place.

Memory testing

Take any subject that it is possible

to look at. This could be a photograph, building, person etc. Look at what it

is you are interested in and try and remember as many details as possible. Try

and take a break from looking and examine how many details you can see in your

head. Once you feel confident that you can remember certain things,

now try and make a drawing of what you can remember. (Of course you are not

allowed to do this drawing by cheating, once you have looked and remembered don’t

look back). Think of Gainsborough and his flights of stairs.

Build this drawing over time, going

back to the source when you cant remember any more.

Part two

Do the same exercise but this time you

can only build relationships such as angles between things or the main masses

of darks or lights. Do not draw things, just how things relate to each other.

You should now begin to see the

relationship between looking, feeling, memory, and responding having made a

collection of marks that begin to ‘resemble’ your subject. These drawings will

be somewhere between abstraction and representation.

Use your critical ability to keep

extending possibilities. Is this a clichéd mark? If so what can I do to be more

inventive? Am I discovering something? If so what?

All good drawing is a discovery, most

of it is of course making images that can be tested against each other and as

this happens new languages are formed.

Sharp looking

As a subject use any object or view

that has interesting contour edges. This could be the human figure, the horizon

of a landscape, edges of objects around part of the room etc.

The aim is to produce an analytical,

well observed, detailed drawing of contours by using only short straight lines.

This drawing should require you to slow down the process of looking. You will

need to look.. make a decision… make a mark… look… make a decision… make a

mark.

Use a very sharp pencil, making all

your marks from the wrist. Non of your marks should be bigger than 1cm and some

as small as 2mm. Start by making a short

sharp, intense mark. Make a second then a third mark, slightly overlapping each

successive mark so that they become linked into a continuous contour. Continue

making these marks to define your first contour edge. Keep these marks as sharp

and intense as possible. Don’t let the pencil become blunt. If you need to, rub

out with a sharp edge of a plastic rubber and re-insert as you go along. Draw

around curves even small ones with small straight lines and change direction of

these lines to find the curve. As you develop the drawing find your way into

internal forms, looking for shapes, perhaps edges of shadows as much as objects

themselves. As you develop the ‘boxing in’ of the drawing, start to think about

mark weight, some areas might need to be slightly lighter than others, others

darker, this will make you develop your ‘touch’ and allow for a greater

understanding of atmospheric perspective in relation to edge/mass

relationships. (In atmospheric perspective, sharp dark marks tend to come

forward and lighter marks sit back into the picture surface) Start doing this

with large forms and as you progress work towards smaller shapes.

Repeat the above and this time start

to build hatching strokes into the drawing in order to define tonal variation.

These drawings should develop careful

and decisive looking. As a result of slowing the process down, your decision

making should have become noticeably more accurate.

3. Technical

approaches

Technical approaches to drawing can

produce very powerful and convincing images. (For instance in the recent Henry

Moore exhibition of Denis Oppenheim’s work, there were large technical drawings of his proposed machines) However there are several

approaches to this and each one gives you a totally different end result.

Start by choosing an existing drawing,

this can be of anything, because it is the format chosen that will shape the

drawing and give you a new image.

Start by making a flat gridded sheet

of paper and on this plot a plan view of your chosen drawing. Then make a side

view of it. If your drawing appears to you as flat, don’t worry, try and

invent some high points and low points and then try and do this with a plan

view as if cut through the centre and then on the furthest side away from you.

These drawings in themselves may already be interesting.

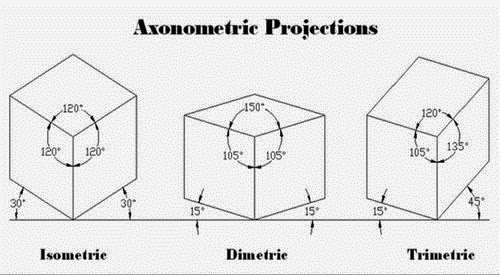

Use the information gathered to try

and make four Axonometric

projections, including isometric, diametric, trimetric and oblique. By making drawings of plan and elevations

of your work you will have already developed some Orthographic projections.

Oblique projection

Once you have the

idea of these four different ways of doing technical projections start to make

a large drawing (at least 2xA1) that stretches your understanding of how an

existing flat drawing can be pulled into an axonometric space. Try to think

about atmospheric perspective and mark diversity as you build these drawings in

order to keep your mark-making invention subtle and purposeful.

4. Finding the core

If you are having

problems working from photographic imagery you could try this exercise. Cut 20

sheets of A5 good quality watercolour paper from existing A1 stock. Mix at

least 6 grades of grey ink, going from very light to dark almost black. Keep

each tonal grade separate. Select six watercolour brushes of different sizes.

Working from a

selected images work quickly using the largest brush and the lightest ink on 10

sheets of your paper. Try and capture the essence of the image but do not get

into detail. Do this again on the next 10 sheets this time working wet on wet.

I.e. dampen your papers before using them.

By the time you have

finished the last wet on wet image the first of your initial 10 images should

be dry enough to work over.

Before doing this

however look at all the drawings you have done and see if any are interesting

in their present state, if so remove from the pile and keep for later.

This time select the

next tonal value one step darker and repeat the process using a slightly

smaller brush. Again work quickly, this time you have a faint image to guide

you and this should help your positioning of mark and tone. Once all 20 are

done, (wet on wet images might need re-dampening) again line them up and select

out any interesting ones, then move on to the next darkest ink and next

smallest brush. Keep doing this until you have used the darkest tone. Now put

up an exhibition of all 20 images.

PS When I first did

this we worked with 50 starting images, so if you are feeling ambitious up the

numbers.

On completion you will have a series of images of varying tonality and with

a variety of mark qualities. Hopefully this series of images will allow you to

start to develop a personal language with which to deal with photographs within

a drawing context. One of the biggest issues with a photograph is what is often

called the ‘tyranny of the image’. It is sometimes very hard to break through

the ‘it looks like a photograph’ barrier. Once you have made these images, some

of the worst ones could be re-cycled again, this time working on top of them

with pen and ink.

Losing and finding

Take any of your existing images that are on paper, (in particular ones

that you don’t think work or are poor) stretch them* and when dry, paint over

them using slightly diluted emulsion or use white chalk on dry paper to do a

similar thing. You should be able to see a ghost of your old image underneath.

Now start picking out what you feel was most important about that image and

re-draw using whatever materials interest you. (Ink and brush, pencils and oil

pastel, charcoal and graphite etc.)

If you think of a drawing as the creation of a problem which is then

solved, then what you are doing is discovering a problem starting with, “why is

this drawing not good enough?” What remains is then the struggle to reveal what

the drawing is becoming about as well as what it was about. This is a type of

compacted time, the compacted image that results being about resurrection and

re-establishment.

What you will gain from this is a process for rescuing drawings that might

otherwise be discarded. It will also allow you to value mistakes and use them

as a tool to enable you to make progress.

“Drawings reveal the process of their own making, their own looking” John

Berger

*How to stretch paper

If you have never stretched paper before there are lots of useful videos on

YouTube such as: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=X_uedfZuvXo (Also read the comments below, as people have picked up common problems)

My tips would be make sure you use good quality brown gum strip tape, (don’t

try and use masking tape) and a large plywood board that has been thoroughly

washed beforehand to make sure no binding glue is left in the top layers of the

wood. I have also found it useful to only wet the gun-strip lightly as too much

water means it slides away from the paper as it pulls tight.

After looking at the basic languages of drawing you can try out the implications by designing your own drawing exercises.

See:

Is drawing a language?