Dog prints

Snow print of a mouse being attacked by a bird

Dinosaur tracks

Sand drawing made by a puffer fish

The puffer fish must have at some point back in its evolutionary history have seen marks made in the sand by an involuntary contact with its body, but how did it move from that to be able to construct such 'sophisticated' looking images?

Bear claw marks

Bear markings on trees are long-lasting and allow for the identification of their travel corridors. Scent markings do a similar job.

The bower bird

The bower bird builds structures according to a particular identifiable aesthetic and decorates these structures with found objects. Like the puffer fish this is part of an elaborate mating ritual.

Within the strictures of Object Orientated Ontology, the reality, agency, and “private lives” of nonhuman (and nonliving) entities, (all of which are considered as "objects"), are taken very seriously. The whole point of 'OOO' as a philosophy is to rebalance the books so to speak. What Object Orientated Ontology is proposing to do is to help us to step outside of our human centred framework and to consider how things might be if everything was simply about 'objects'. For example, the 'life' of a stone is a life that inhabits its own timeframe, a timeframe that we as humans would not be able to understand or perceive, our lives in comparison to a stone's existence being as short as a mayfly. The situations that I have presented above are however still presented from a 'human' centred viewpoint, something that I would as a human find impossible to do otherwise. However by thinking about these things, perhaps we will be less inclined to just use the world as if we own it, or as if all the other things that are not me are in some way less important than me. The real lesson that the puffer fish example has to teach us is that the puffer fish will make its patterns with or without any human observations as to whether or not its world is interesting or not.

Graham Harman, one of the key writers in relation to 'OOO' states, “The world is not the world as manifest to humans; to think a reality beyond our thinking is not nonsense, but obligatory.”

Therefore the traces of physical actions left in inanimate objects as they come into being could also be thought of in this context as drawings.

A wind weathered rock

In the case above different hardness of rock types has meant that wind weathering has eroded some surfaces more than others. The action, or coming together of wind and rock, has resulted in a change of surface, this 'trace' of the action, within an 'OOO' framework would in effect be a drawing.

As I think about these things I'm also drawing. In this case using charcoal on paper. The carbon complexity called myself, in this case engaging with the much purer carbon of charcoal in such a way that vigorous rubbing has occurred between the burnt wood and a rough Indian rag paper. This has happened over a period of human measured time (a morning) in order to produce several versions, which are now themselves entering a new timeframe of paper/charcoal, one which will itself depend on whether these drawings end up as landfill or in a national art collection.

Studio view

I doubt if these drawings will see the light of day ever again, but the thinking process that allows me to decide to draw a lump of stuff as if it could be aware is hopefully going to eventually allow me to produce much more interconnected pieces of work, perhaps less formal and more process aware.

Maringka

Tunkin, Freda Brady and Yaritji Tingila Young are artists from Alice Springs.

They work in a tradition that goes back a long way.

Maringka Tunkin, Freda Brady and Yaritji Tingila Young in front of one of their paintings

The tradition that these artists have emerged from did not treat everything as if it belonged to separate categories. In their conceptual map of the situation, animals, landscapes, people and events are all one interconnected 'hyper-object' called the 'Dreamtime'. But their existence is also one that rubs up against a very different 'hyper-object', the 'Western art world', a complex of artists, dealers, critics, buyers and value sets that are just as real as the 'Dreamtime' but far less nourishing. The concept of 'hyperobjects' is taken from Timothy Morton's book of the same name. 'Hyperobjects' as an idea is another offshoot from 'object orientated ontology' and allows us to deal with , as Morton states, "things that are massively distributed in time and space relative to humans". Maringka Tunkin, Freda Brady and Yaritji Tingila Young will also have to confront other 'hyper-objects' in their lives, such as global warming, the Australian economy and academic anthropology. Within the framework of object orientated ontology systems and processes are regarded as things, or objects, so that people, rocks, animals, star systems and mathematics are all seen as realities that bump into each other, but so are things such as Sherlock Holmes or Harry Potter. What becomes important is the resistance or actions that occur as one thing meets another. This point of resistance is often seen as the 'politics' of the situation. Therefore if you are operating as an artist within a situation that is being looked at through an 'OOO' lens, you would attempt to be more attentive to the physical objects and processes involved in your immediate environment, as well as the 'hyperobjects' that you may well find yourself part of.

This area of thinking, often associated with speculative realism, is a critique of the way philosophy has developed since Kant. Kant by developing the duality of the noumenal (the world as it is "in-itself") and the phenomenal (the world as it appears to us) set philosophy on a path that would essentially be about how human beings think about things, and therefore 'reality' sort of retreated behind a mist, it was something to think about, see at a distance, but never really experience. The rise of phenomenology began to open out the idea of 'embodied' thinking and once it began to be accepted that the physical reality of living in the world was itself constructing what it was to understand existence, then the doors were open for a way of critiquing all our mental constructions about reality. In particular ones that either reduce it to tiny bits, such as everything is really composed of atoms or wave particles, or ideas that seek to make everything fit into a bigger picture, such as God, or Nature. What we deal with is what we deal with. When I see a stone and pick it up, I can't see its atoms, I deal with its stoneness and at the same time it is dealing with my picking of it up. This is not to say atoms are not real, but that atoms are to be considered as things or objects in their own right and in their own world. A dog is a dog and the atoms that make up a tiny portion of a hair on the dog's head are just atoms, and will be experienced in a world that is commensurate with atoms, one which in human terms would include instruments such as electron microscopes.

Object orientated ontology has diagrams and as this is a drawing blog, I shall put one in. Harman presents us with 'real' objects and 'sensual' objects, as opposed to Kant's noumenon and phenomenon. The noumenon is a posited object or event that exists independently of human sense and/or perception. The term noumenon is generally used when contrasted with, or in relation to, the term phenomenon, which refers to anything that can be apprehended by or is an object of the senses . So in Harman's case real = noumenon and sensual = phenomenon. But there are essential differences. In Harman's view both real and sensual objects can interact with each other, hence the diagram below. In Kant's view the noumenon is a hypothesis and the only contact we have with reality is via sense impressions, or phenomenon, so we have no actual way of saying anything about reality itself.

I have found some aspects of 'OOO' very useful as a visualisation trigger, and some of the drawings that have resulted are I think interesting, but my personal use of 'OOO' like all theories, is I'm afraid somewhat selfish. I only use the bits I find useful and don't attempt to get to grips with the aspects of the theory that don't seem to help me visualise things. This would be a real problem if I was to turn to philosophy as a trade. However, I read 'OOO' as just another 'hyperobject' and what I'm enjoying trying to visualise are the points of resistance as 'OOO' comes up against other objects and systems such as the city of Leeds, the people that live in Chapeltown, toothache, getting older, a very cold spring, Brexit and a series of images that I have been making and thinking about over the last 5 years.

I found it interesting to use the diagram above in relation to my thoughts about Bruno Latour's observations on scientific methodology below.

There is a description of how scientists think about soil analysis by Bruno Latour in his book ‘Pandora’s Hope’ (1999, p. 56), and I have found it very useful as a way of thinking through how as an artist you can research into a subject and how as you do so you focus on various aspects of it. It allowed me to accept that I can generate thoughts about possible ideas and forms that connect or link or illustrate an individual aspect of that research, without having to prove how each aspect of my thinking links up or creates an effect on any larger entity. Each thing I do can be seen as autonomous and something I can focus on until I’m satisfied that it does what I want it to do. An idea can have its own form and material structure, as well as being related to whatever things stimulated it in the first place. Latour’s description helped me to accept that each idea can be seen as an entity in its own right, and that I didn’t have to try and deal with everything at once or prove that in some way the work bore some sort of responsibility to what was its initial reference. There is a sort of flattening out of responsibility, an idea is as much an object as an element of research, which is just as much of an object as a person, a town or a philosophy.

Latour says that the scientist will begin research with an awareness that it is soil that is being examined. Soil as a generic entity; that stuff that is more than just dirt, which has substance and is expected to be able to support plant growth. However what the scientist wants to examine is not this big entity but something else, something more focused and so work begins to focus down and as this happens, soil as a generic entity disappears from view and new forms come into the frame. An area of soil is usually gridded with string and pegs, so that the surface of the soil can be numbered and referenced, in order that any differences in soil acidity or alkalinity in terms of location of ‘hot spots’ or changes in average ph can be recorded. The scientist is now examining a grid of relationships that were not there before. It could be argued that the unruly nature of the soil has now been tamed, the ‘wildness’ has been removed and this new structure allows other things to be done. This is similar to what happens when I’m drawing from observation. My drawings can’t include everything, so I make a selection and this selection is what will allow me to develop a next stage of an idea. The grid that the scientist uses is also familiar to me, as a student I was taught to apply a grid of looking to make sure that I was able to accurately measure relationships and I still mentally apply this as I draw, checking horizontal and vertical alignments automatically as I make decisions as to what goes where in the drawing.

A scientist would now use the grid to enable a series of soil samples to be taken in such a way that each sample had a clear reference that could refer back to an exact location. A “pedocomparator” is then used to take soil samples. What is interesting here is that the generic soil could be seen as matter, but as it is gridded it then takes on a particular form, which becomes the object of attention, but now that the “pedocomparator” comes into play the material inside each gridded section is the focus of attention; form as the focus of attention is replaced by matter again. A process of reduction is taking place, but one that produces a definite something at each stage. I take my drawings from observation back into the studio, I then work from them, looking for new connections, trying to find forms that will work within a different set of relationships. Instead of drawings about spatial and formal observations, the drawings become about other narratives and connections that lie outside of the perimeters of the first experience. This is similar to the use of the “pedocomparator” (a device for arranging and comparing soil samples), as an instrument it brings to the location a set of attributes taken from the scientist’s laboratory, as opposed to the artist’s studio.

The soil samples taken from the various gridded sections are now organised into a set of gridded relationships that go to form a diagram that displays a set of interrelationships between samples. So we now have a new form, one that can be looked at and used to develop further thoughts or ideas. Just as the scientist has produced a new image that will allow decisions to be made, the artist’s images that have been developed from the initial observational drawings are now subject to contemplation and will result in further ideas and thoughts about possible formats for development.

The scientist’s diagram now becomes a medium for analysis. What is important here is that it is the diagram that is analysed, not the soil. There is of course a direct series of connections back to the soil but as the scientist concentrates on the diagram, the diagram is the thing or object of study, not the soil. Similarly in the studio, the new images that are emerging are objects in their own right, things that have emerged in a process of abstraction and which are connected in process back to the initial observations, but are now a product of the processes of art, just as the scientist’s analysis of the diagram is now a process belonging to science. The writing up of a report based on the diagram gives the process yet another new form, myself as the artist am now making a series of images for exhibition and am also creating new forms. Each of these processes can be seen as a stand alone ‘object’ and what Latour and others would argue when experienced they are types of realities not things either reducible to atomistic bits or to be described as components of some sort of overarching bigger picture. The soil is still of course soil, the landscape or situation drawn by the artist still remains as the landscape, but the diagram is just as much an object as the drawing, they are all interconnected and rich in their interconnections but each is to be experienced as a thing in itself.

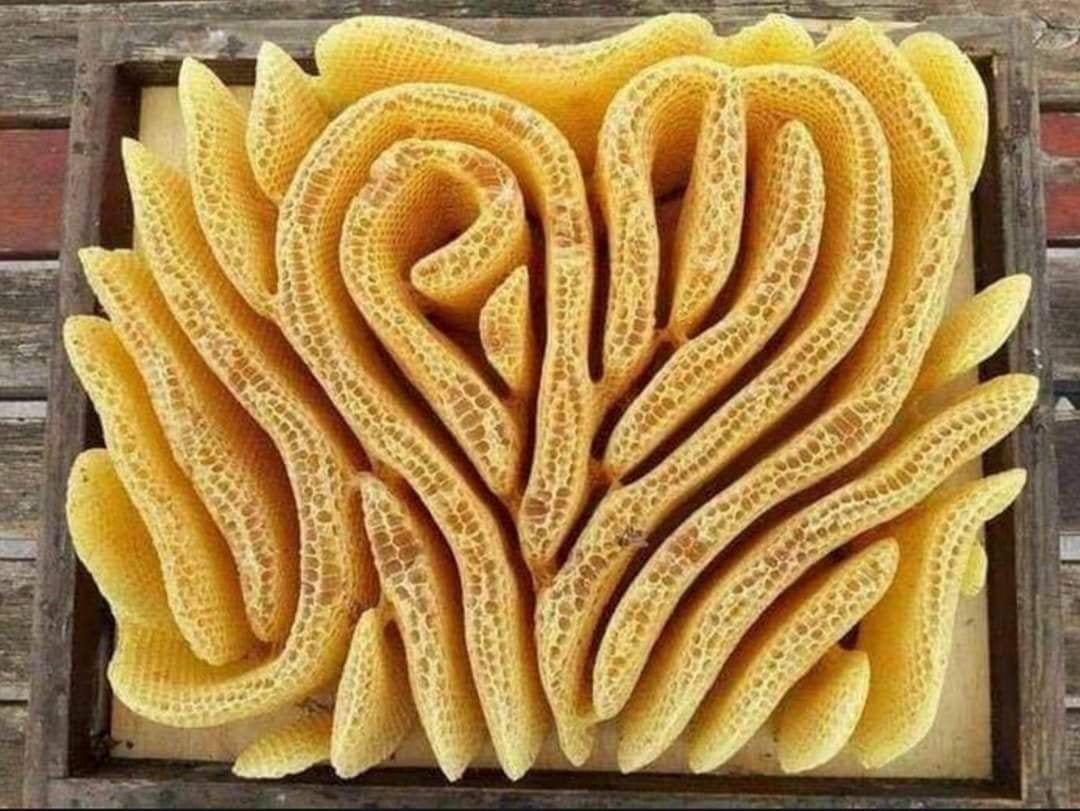

Perhaps best to leave the last word to the bees.

I found it interesting to use the diagram above in relation to my thoughts about Bruno Latour's observations on scientific methodology below.

There is a description of how scientists think about soil analysis by Bruno Latour in his book ‘Pandora’s Hope’ (1999, p. 56), and I have found it very useful as a way of thinking through how as an artist you can research into a subject and how as you do so you focus on various aspects of it. It allowed me to accept that I can generate thoughts about possible ideas and forms that connect or link or illustrate an individual aspect of that research, without having to prove how each aspect of my thinking links up or creates an effect on any larger entity. Each thing I do can be seen as autonomous and something I can focus on until I’m satisfied that it does what I want it to do. An idea can have its own form and material structure, as well as being related to whatever things stimulated it in the first place. Latour’s description helped me to accept that each idea can be seen as an entity in its own right, and that I didn’t have to try and deal with everything at once or prove that in some way the work bore some sort of responsibility to what was its initial reference. There is a sort of flattening out of responsibility, an idea is as much an object as an element of research, which is just as much of an object as a person, a town or a philosophy.

Latour says that the scientist will begin research with an awareness that it is soil that is being examined. Soil as a generic entity; that stuff that is more than just dirt, which has substance and is expected to be able to support plant growth. However what the scientist wants to examine is not this big entity but something else, something more focused and so work begins to focus down and as this happens, soil as a generic entity disappears from view and new forms come into the frame. An area of soil is usually gridded with string and pegs, so that the surface of the soil can be numbered and referenced, in order that any differences in soil acidity or alkalinity in terms of location of ‘hot spots’ or changes in average ph can be recorded. The scientist is now examining a grid of relationships that were not there before. It could be argued that the unruly nature of the soil has now been tamed, the ‘wildness’ has been removed and this new structure allows other things to be done. This is similar to what happens when I’m drawing from observation. My drawings can’t include everything, so I make a selection and this selection is what will allow me to develop a next stage of an idea. The grid that the scientist uses is also familiar to me, as a student I was taught to apply a grid of looking to make sure that I was able to accurately measure relationships and I still mentally apply this as I draw, checking horizontal and vertical alignments automatically as I make decisions as to what goes where in the drawing.

A scientist would now use the grid to enable a series of soil samples to be taken in such a way that each sample had a clear reference that could refer back to an exact location. A “pedocomparator” is then used to take soil samples. What is interesting here is that the generic soil could be seen as matter, but as it is gridded it then takes on a particular form, which becomes the object of attention, but now that the “pedocomparator” comes into play the material inside each gridded section is the focus of attention; form as the focus of attention is replaced by matter again. A process of reduction is taking place, but one that produces a definite something at each stage. I take my drawings from observation back into the studio, I then work from them, looking for new connections, trying to find forms that will work within a different set of relationships. Instead of drawings about spatial and formal observations, the drawings become about other narratives and connections that lie outside of the perimeters of the first experience. This is similar to the use of the “pedocomparator” (a device for arranging and comparing soil samples), as an instrument it brings to the location a set of attributes taken from the scientist’s laboratory, as opposed to the artist’s studio.

The soil samples taken from the various gridded sections are now organised into a set of gridded relationships that go to form a diagram that displays a set of interrelationships between samples. So we now have a new form, one that can be looked at and used to develop further thoughts or ideas. Just as the scientist has produced a new image that will allow decisions to be made, the artist’s images that have been developed from the initial observational drawings are now subject to contemplation and will result in further ideas and thoughts about possible formats for development.

The scientist’s diagram now becomes a medium for analysis. What is important here is that it is the diagram that is analysed, not the soil. There is of course a direct series of connections back to the soil but as the scientist concentrates on the diagram, the diagram is the thing or object of study, not the soil. Similarly in the studio, the new images that are emerging are objects in their own right, things that have emerged in a process of abstraction and which are connected in process back to the initial observations, but are now a product of the processes of art, just as the scientist’s analysis of the diagram is now a process belonging to science. The writing up of a report based on the diagram gives the process yet another new form, myself as the artist am now making a series of images for exhibition and am also creating new forms. Each of these processes can be seen as a stand alone ‘object’ and what Latour and others would argue when experienced they are types of realities not things either reducible to atomistic bits or to be described as components of some sort of overarching bigger picture. The soil is still of course soil, the landscape or situation drawn by the artist still remains as the landscape, but the diagram is just as much an object as the drawing, they are all interconnected and rich in their interconnections but each is to be experienced as a thing in itself.

Perhaps best to leave the last word to the bees.

When a beekeeper forgot to put the frames back in a hive, bees built this amazing structure themselves. It takes into account airflow and temperature regulation.

If you are interested in finding more out about how object orientated ontology, speculative realism, actor network theory, agential realism or material thinking could help you think about your relationship with drawing and the world, the following bibliography could be a useful starting point.

Barad, K (2007) Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning New York: Duke University Press

Bennett, J (2010) Vibrant Matter: A political ecology of things New York: Duke University Press

Bogost, I. (2012). Alien Phenomenology. Ann Arbor, MI: Open Humanities Press

Harman, G. (2011). The Quadruple Object. United Kingdom: Zero Books

Latour, B (2017) Facing Gaia London: Polity Press

Latour, B. (1999) Pandora’s Hope Cambridge, Mass: Harvard Press

Morton, T. (2013) Hyperobjects: Philosophy and Ecology after the End of the World. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press

There is an interesting dictionary of OOO terms available that also links to suggestions as to how to read the diagram of Ten Possible Links above.

How OOO is effecting contemporary art practice

See also

Drawing and philosophy part 4

If you are interested in finding more out about how object orientated ontology, speculative realism, actor network theory, agential realism or material thinking could help you think about your relationship with drawing and the world, the following bibliography could be a useful starting point.

Barad, K (2007) Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning New York: Duke University Press

Bennett, J (2010) Vibrant Matter: A political ecology of things New York: Duke University Press

Bogost, I. (2012). Alien Phenomenology. Ann Arbor, MI: Open Humanities Press

Harman, G. (2011). The Quadruple Object. United Kingdom: Zero Books

Latour, B (2017) Facing Gaia London: Polity Press

Latour, B. (1999) Pandora’s Hope Cambridge, Mass: Harvard Press

Morton, T. (2013) Hyperobjects: Philosophy and Ecology after the End of the World. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press

There is an interesting dictionary of OOO terms available that also links to suggestions as to how to read the diagram of Ten Possible Links above.

How OOO is effecting contemporary art practice

See also

Drawing and philosophy part 4