In a city a straight line is something you confront on a daily basis, and it is central to our western European view of the world. Engineering and architecture both rely on the straight lines of geometry. Every room we enter has straight edges to it, if not it is something of an oddity, for instance Gaudi's architectural visions are seen as just that, 'strange visions', rather than the norm. Contrast this situation with the architecture of Burkina Faso.

The straight line is an idea, a construct and as such it carries within it a densely compacted body of information that comes from its history.

The first straight lines produced by human beings would have been made with threads. The easiest line to make would be for someone to pull a thread held or tied at the other end, until it tightened. The tightened thread would make a perfectly straight path.

Once understood as a principle, the next step would be to stick a length of wood into the ground. Do the same with a 2nd length at a set distance. Tie a thread between the two points and tighten, then that could be checked by looking along the line to see a straight. Once this principle was understood, you didn't need the string or thread any more because now the line was also an idea and you could 'sight' a line by lining up two things.

Geometry begins with string, imagine the nails as posts set into the ground, huge 'sacred geometry' forms are then easy to envisage.

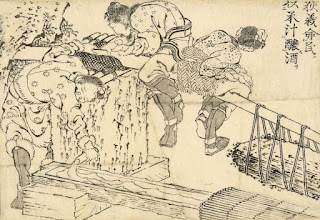

The Nazca peoples checked the straightness of their drawing lines through the landscape by putting a notch or hole in a length of wood pushed into the ground and using that to 'sight' another pole set into the ground at a distance. Stones could then be moved into place whilst someone siting the straight shouted instructions or indicated using arm movements, whether to move them to the left or right.

Nazca lines

To make a perfectly vertical straight line, find a high point, such as a tree branch, tie a thread or string to it, and tie a heavy object at its other end. The path that the string runs through is always perfectly straight. This has been used to check whether a building's wall is upright at 90 degrees or a right angle, for thousands of years. We now call the tools for doing this a plumb bob and line.

Plumb bob and line

We live in spaces often defined by straight lines and because we know them to be straight, we also believe we see them as straights. I was first made aware of this by a drawing tutor, who would stand behind us with a long straight edge, he would hold it above our heads and advance it slowly until we could see its ends via peripheral vision. Suddenly its shape came into vision and it was a curve, but as it was pushed further forward and we could recognise it 'properly' as a length of 2 x 2 timber it reverted to being straight.

Any straight seen, is seen by you as from the centre of a sphere.

We in effect 'see' what we think is there and not what is actually there. The attempt to look at a straight line and actually measure it and draw it is such a basic activity, that it is rarely done, because it is in effect questioning everything we see.

A drawing produced by someone looking at a straight edge set at right angles to them as in the line AB above.

Because the straight line is such a powerful idea, it can also be used to think about what ideas are and about what sort of ideas can be carried within visual constructions like lines or angles.

The artist Cornelia Parker is a conceptual thinker. She likes making art that asks questions. She at one time made a series of self portraits using her own blood to draw basic forms, such as 'Self Portrait as a Line'.

Cornelia Parker: Self portrait as a line

We think about the use of our own blood in very particular ways, for instance it reminds us of self-sacrifice, and ideas such as the transmutation of the body as in Christianity. The line is such an essential idea, it is suggested by Parker, that it is as a concept in a similar category to some aspects of religion. A straight line doesn't exist outside of the idea of it and the same could be said of religion, these things are all in our minds.

Marcel Duchamp is often credited with the invention of conceptual art, (not that any one person could ever really be credited with such an idea, because the majority of art is and has always been conceptual, but perhaps this argument is for another day), and one of his earliest pieces was made as a response to the power of the measured straight line.

But first of all a bit of history. The Egyptians defined the 'Royal Cubit' as the length of the ruling Pharaoh’s forearm and hand. They had very big building projects and needed clear measurements in order to communicate ideas. The cubit was only a cubit if it existed along a straight line. A yard was originally the length of a man's belt, something that could like the string, be pulled straight in order to act as a measure. In the 12th century, King Henry I of England fixed the yard as the distance from his nose to the thumb of his out-stretched arm. These 'rulers' would come and go but eventually the meter was decided upon as the standard we should all use because it was now science that ruled. First defined by the French Academy of Sciences as 1/10,000,000 of one half of a meridian, (the shortest distance from the North Pole to the Equator), after checking this, a platinum bar was made as the prototype meter for this new official distance which became known as the “mètre des Archives” and it was stored in the French National Archives. For every day use the meter was now literally set in stone, the “mètre étalon” being a small shelf of marble installed beneath the arcade at 36, rue Vaugirard, right across from the Senate at the Palais du Luxembourg.

The mètre étalon

Duchamp's response to this was to cast aspersions on all this scientific decision making and to create his own versions of the metre. He had read of Alfred Jarry's 'Pataphysics' a concept that took the idea of science and bent it until it was broken by sex and other human emotions. 'Three Standard Stoppages' was an idea first constructed in 1914 and it consisted of a materialised idea. The idea was this: To take three metre lengths of thread and to drop them from a one metre height. Each length on landing was traced around and the tracing used as a template from which to cut a wooden 'ruler'. These three rulers and the threads would then be presented in a specially designed case, made to look as if it was of a similar sort to those already in use as 'metre checks' throughout France.

Duchamp: Three Standard Stoppages

In England we had our own inch, feet and yard system, one that had to also be fixed.

British standard lengths set in a wall at Greenwich

Alongside the British standard lengths there are protrusions around which a length of string could be wound so that a 'straight' line can be stretched between two points and the measure taken away. The nearest equivalent site to where we are in Leeds is in Bradford city centre. The Standards of Imperial Measurement are to be found on plaques situated behind the statue of Queen Victoria, just over the road from the Media Museum.

Bradford city centre: Standards of Imperial Measurement

All of these constructions would be unthinkable without the idea of the straight line. Perhaps it is time to look around you and to think about where these lines exist and what they might signify. In common present day language 'straight edge' means having an ascetic or abstinent lifestyle; hippy culture was often presented as bright psychedelic swirls; it is interesting how our visual language is often used to present lifestyle choices, think of those 'beige' people, those that are normal to the point of being bland.

Lines in drawings are capable of so much more than just length measurement. Their materiality includes the substances of making, such Vic Muniz’s lines rendered in runny chocolate sauce when making a drawing of Jackson Pollock at work, or Motoi Yamamoto's intricate line mazes of salt.

Motoi Yamamoto

Do we think enough about the materials we use to make lines with? Sugar lines are so different to salt lines, pencil lines so different to those made using ink.

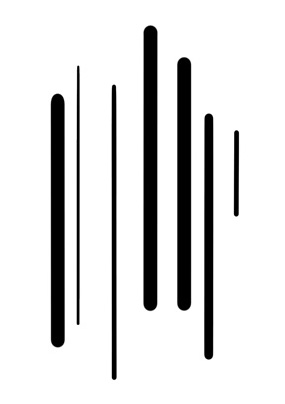

A line also has direction, Vertical lines are straight up and down lines that are moving in space without any angular direction and are perpendicular to horizontal lines. They suggest height, uprightness, good health and strength. Width variation can suggest their moving backwards and forwards in space.

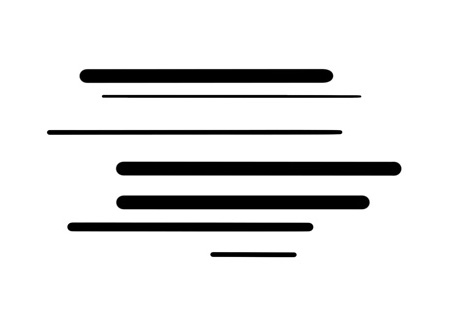

Horizontal lines are straight lines parallel to the horizon that move from left to right. They suggest width, distance, calmness, rest and stability, but also lying down, sleep and death.

But what if the line has a certain quality to it?

Are these straight lines capable of holding ideas about emotional states or sounds or ...?

A straight line drawn at an angle

This is a case of going back to square one. This post is a reminder that as we draw more we tend to forget the basics and in doing so lose track of what we are doing and the possibilities for communication.

See also:

Drawing measuring and the body

Mathematical shapes of interest

Drawing with alternative materials

Oak gall ink

Graphite

Dotted lines

Signs of life in flowing line drawings

Technical drawing