The notion of 'qualia' is of central interest to anyone involved in making drawings about perception and trying to theorise about them. As a technical term it sits within a sub-set of language developed to deal with philosophical concepts. In this case phenomenology.

I'm fascinated in the use of this word, perhaps because I'm very suspicious of words in the first place. I tend to think that in their very definitions they cut us away from the actual experiences we have. For instance, the word apple in no way helps me to explain the relationship I have with the experience of it. Of course most people would argue that it is in using the syntax of language and the sentences it helps us construct, to explain the particular experience I had with the apple, that words come into their own as a way to help us communicate to each other. But what I would argue, is that because each language is media specific and what it communicates is mainly something about that specific language, we have a problem. In this case we have a language made up of words; therefore the word, 'qualia' goes right to the heart of the problem. 'Qualia' is the plural of 'quale', which means that within this sub-set of language an assumption is already in place that the sensations that form experiences come packaged together as bundles, rather than as individually identifiable components. But in order to understand 'qualia' as particular types of sensations, we have to remember that these bundles of experiential data are based on 'a quality or property as perceived or experienced by a person', or, 'individual instances of subjective conscious experience'. Once again words tend to be problematic, because this is a process, not a set of things. In the middle of this I would though like to throw in a question as to whether or not 'qualia' are only experienced by humans? The word is derived from the Latin neuter plural form 'qualia' of the Latin adjective 'quālis' meaning 'of what sort' or 'of what kind' but always in specific instances, such as "the sensation of what it is like to taste this particular apple now". The word tending to put a focus on the human experience of sensations rather than the quality of the sensations themselves. Many will argue that you cant separate the two but the fact that words allow you to do this, in some ways flags up the problem with words as experiential atomisers.

Qualia, and those feelings and experiences we have of them, come in all sorts of formats, and these depend on the way our body works. We have looked for example at how we use a mobile phone in relation to the various uses of our touch sensors. Qualia can also be the sensations of colour perception or a feeling, such as sorrow or anger; a mental state can itself provide qualia, as can a feeling of hunger or pain. I am in each case experiencing a phenomena that I 'know' or 'sense' in some way as being unique. It feels like this rather than that and is an introspectively accessible, phenomenal aspect of what some people would argue is my mental life, but which I am beginning to think might not be just to do with me, but to do with the entanglement of myself into the wider world.

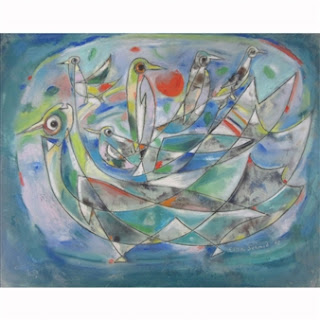

The status of qualia are hotly debated in philosophy largely because they are central to a proper understanding of the nature of consciousness. Qualia are at the very heart of the mind-body problem and because of this, I have decided to try and build a series of representations that will allow me to both externalise my thinking about them and to begin a process of communication with others as to the possibility of qualia to operate as representational hinges for those sensations that operate between reality and its perception and in particular the perception of the interior life of our own bodies.

I have made quite a few drawings using these forms and have been looking at how as a language, their relationships can be learnt as a sort of code that stands for various somatic feelings. Even though this is a project in its early stage, it feels to me as if it has many possibilities in the opening out of an approach to finding a language to talk about feelings, such as pain, itchiness, loneliness, hunger, the need to go to the toilet or to indicate indigestion or a heart beating too quickly.

Heinrich Klüver extrapolated four groups of entoptic visual phenomena that he called 'Form Constants'; these were, lattices, cobwebs, tunnels, and spirals. More recently it has been theorised that structures of neural interconnectivity could dictate the type of emergent phenomena that can be produced. Neural network models of geometric hallucinations have gradually incorporated empirical insights from neural anatomy and physiology, including the spatial arrangement of different neuronal cell types.