Speed has some interesting observations and is very

opinionated when it comes to critiquing other artists. The book reads as if it

comes from another world, an age well before modernism, but you need to remember that

Cubism and early abstraction were already well established in mainland Europe

when it was written.

However when he gets to unpicking why he doesn’t like

academic approaches to drawing he has this to say about too much precision.

‘There must

be enough play between the vital parts to allow of some movement;

"dither" is, I believe, the Scotch word for it. The piston must be

allowed some play in the opening of the cylinder through which it passes, or it

will not be able to move and show any life. And the axles of the wheels in

their sockets, and, in fact, all parts of the machine where life and movement

are to occur, must have this play, this "dither." It has always

seemed to me that the accurately fitting engine was like a good academic

drawing, in a way a perfect piece of workmanship, but lifeless. Imperfectly

perfect, because there was no room left for the play of life. And to carry the

simile further, if you allow too great a play between the parts, so that they

fit one over the other too loosely, the engine will lose power and become a

poor rickety thing. There must be the smallest amount of play that will allow

of its working. And the more perfectly made the engine, the less will the

amount of this "dither" be’.

The concept

of a drawing having life comes up yet again, as it did in the previous post. In this case Speed comes up with

the idea of ‘dither’ to explain it. However he also warns against too much ‘dither’.

I can see

what he means, energetic markmaking for its own sake can become a mannerism and

when it does a drawing begins to lose authenticity.

I think

Speed’s book is a salutary read. It comes from a time when people could have

firm convictions as to what is right and wrong about art, convictions now long

denounced as outdated and obsolete in this time of post-post-modernism.

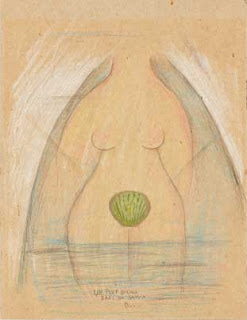

His

sections on composition like the one illustrated above, take me right back to school and those art classes

whereby we had to draw out the various underlying dynamics and geometries of a

painting’s structure.

Even though

no longer taught (well not in most undergraduate Fine Art courses in England),

it is still useful to go back and look at how an awareness of these things was

achieved. I have seen so many poorly composed images or even worse images that

have no conception of a relationship between surface organisation and meaning,

that I personally believe it would do no harm to look again at these things,

even if simply to consign these ideas to history. At least people would be able

to make a decision as to why no compositional construction is needed or how

their approach to constructing a figure differed from more traditional

methods.

Speed

himself saw his approach as being modern. He wanted to free students from the

tight constrictions of the academy. He is one of the direct descendants of the

staff that now teach cutting edge contemporary practice at Goldsmiths. He

indeed uses an example of student work done in classes there to illustrate a

point. I went to art college nearly 60 years after this book was published, the

book is now of course over 100 years old, so my art school experience should

feel as out of date now to contemporary students as his did then to me.

England was

slow to take on the lessons of Modernism, but when it did it took the teaching

of the Bauhaus to heart and the institution I now teach in was at the forefront

of the radical change to art education when it finally happened in the 1950s

and 60s.

However I’m

always worried about throwing out the baby with the bathwater and when you look

back, you can always find things of interest. So why not read this book and see

if there is anything in it that still makes sense to you?

Download here The Practice and Science Of Drawing, by Harold Speed

Compare Speed's book with earlier writings that influenced him.

In particular Hogarth'sThe Analysis of Beauty and SirJoshua Reynolds's Discourses

The further back we go the firmer in their convictions art educators become. As Reynolds states in relation to the setting up of the Royal Academy: 'The student receives at one glance the principles

which many artists have spent their whole lives in ascertaining; and, satisfied

with their effect, is spared the painful investigation by which they come to be

known and fixed. How many men of great natural abilities have been lost

to this nation for want of these advantages?'

Compare this situation to contemporary books on drawing practice. For instance

'Drawing Ambiguity: Beside the Lines of Contemporary Art' published by 'Tracy' the collective name for the centre for recent drawing in 2015, has this to say about drawing;

'A position of ambiguity, a lack of definition, is not only desirable

within fine art drawing but also necessary - having the capacity to enable and

sustain drawing practices.'

See also: