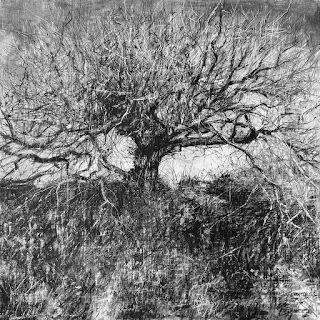

A first and a last drawing for Drawing Dialogue: Moving from an empty page to a full one. Giving space and taking space.

From the Drawing Dialogue exhibition

Last weekend saw a Drawing Dialogue symposium, designed to accompany the Keighley Creative exhibition of work that had been done so far. My contribution was a presentation about the relationship between dots and lines, a subject that reflects my current interest in 'primitives' or the basic building blocks of our visual language. It was very much a 'follow my nose' sort of presentation, but I did write out my main points beforehand, so I thought I might as well host the presentation text on this blog, because a couple of people did ask me if they could get hold of the script I was working from.

Drawing Dialogue is an ongoing project and I have posted about the project in the past. The basic idea is one artist begins a drawing, it is then sent on to another artist, who develops the drawing, and then a third artist is asked to complete it. A form of consequences, or collaborative drawing, that essentially means that each artist has to be sensitive to the needs of others. It is a very interesting exercise in empathy and sensitivity and helps to dissolve artists' egos.

So here is the full text.

A new life for dots.

Drawing Dialogue Symposium

At the core of all our drawing dialogues is the coming together of different drawing languages. In order to explore the implications of these meetings I’ve therefore decided not to focus on one of the actual encounters I’ve taken part in, but to set up an imaginary encounter between points and lines so that you can get some sort of glimpse of the theoretical possibilities that open out within our various collaborations.

Tim Ingold has written extensively on the life of lines, he regards lines as essential to our understanding of life. This is an old idea and it goes back to the Anglo-Saxon idea of the Wyrd, a cosmological idea that has at its centre a vision of life that is shaped by fate.

Cats cradle as life story

Imagine if you will, that on birth you have two umbilical cords, one the physical connection that you have with your mother and another invisible one that connects you to your fate or life. The first one is cut on the day of your birth the other is finally severed on the day of your death.

This line will first of all wrap itself around the family core, mother, father, brother, sister and then around the home, the village and the landscape of childhood. As you get older it will tie itself to and around all the events in your life as a pattern is woven and what was once a single thread becomes a thick blanket of interconnections. This is a wonderful metaphor and it has for myself and many people of the drawing community been a concept that has allowed us to develop ideas, images and ways of working that themselves continue to extend and expand the woven fabric of drawing dialogues.

However although lines are used by most of the artists involved in Drawing Dialogues, lines are themselves second order entities, they are composed of tiny ideas that we call points and it is the life of dots and their uses in image making that I would like to explore today.

All forms of drawing are essentially to do with the imagination, and a dot is at its centre an idea of a point.

A point is what Euclid called a primitive notion, which means that it cannot be defined in terms of a previously defined object; originally Euclid defining the point as "that which has no part". In fact for Euclid points were all about relationships.

Points have relationships and these can generate ideas of space

Points were where things met. A line could meet another line at a point, this point allows us then to build a further construct in the mind, a tiny piece of grit around which pearl like we grow ideas, such as three dimensional space. From this thing that has no part we can build an edifice, the three axes of height, width and depth all come together as a point.

Map of Ghana: Look at the line that separates Ghana from Burkina Faso.

Lines have certain issues that they bring with them, one of the most difficult being that they also operate as boundaries.

When the European nation states were carving up territories they would often do this with maps and rulers; the rule establishing the rule so to speak. Drawn lines would divide peoples from their traditional homelands, would establish new nations consisting of collectives of peoples whose only common issue was that they had been bundled together because of some European game of thrones. We draw lines around things to define them, to fix them in the imagination, this is why so much of our graphic design imagery is sharp edged, fixed by a line often now clarified by Bezier curves as in software programs such as Illustrator or Photoshop.

A car drawn using Illustrator

Perhaps the strangest drawing I know of is the one drawn onto the plaque that was fixed onto the side of the Pioneer 10 space craft. Launched in 1972, it was the first manmade object to be sent out into far space, it was designed to be able to travel beyond our solar system and out into the wider galaxy. A wonderful idea, but not so the line drawing of a man and a woman that accompanied the vessel on its journey. The line drawing of both man and woman is from the front, the man holds his arm up in greeting, showing an open hand, the woman, less active of course, stands beside him. The man has short hair and is clean-shaven, the woman has a longer but coiffured hairstyle.

So many things are wrong with this drawing, from the Eurocentric portrayal of the humans, to the graphic convention of a line representing complex three-dimensional forms. There is no way that any creature on finding this space vehicle entering their star system could deduce any information from these drawings, except that something with some sort of intelligence had had them manufactured. We have been seduced by lines and believe that they can be used to clarify situations. But there is also another problem and that is how lines fix identity and give things a shape that you can put a word to and that word is nearly always a noun. A tree, a stone, a body an arm, a leg.

Words are themselves boundaries and although we find them very useful, we also need to be reminded of their limitations. A tree is also a process and as a process it has no edges. It belongs to the soil as much as to the air. As a squirrel takes an acorn away to bury it, the squirrel become part of the tree’s process, as the rain falls, the tree engages with the weather, allowing some waters to pass through its leaves and others to fall around the edges of itself, selectively watering the surrounding soil for other organisms that have become part of its eco system.

Primary school teaching aid

As you eat that apple, you are participating in the extended process of treeing, your humaning conjoining for a brief time with the life process that we often put a line around and call a tree.

But when you use a dot and I use the word dot rather than point deliberately, you can think about these issues differently.

The edges between things become permeable

A dot has more physical presence than a point. Therefore it can have more of a life of its own and any life form or self-organizing system relies on an ability to interact with its surroundings in order to survive. This ability to self organise is in fact an emergent property of random dynamical systems, that you might think of as chaos. I.e. eventually if you have enough stuff and mix it about long enough at some point order will not just emerge, but a type of order that likes to keep itself in that very order, as well as being able to interact with all the other chaos around it, will come into being.

In order to maintain themselves, these orderly systems possess what are called Markov Blankets. If we go back to our tree, there is a core part of the system that is clearly treeing, but there are other parts of the system that are also raining, humaning, soiling and squirreling. That is, that the tree’s Markov blanket touches and enacts with the Markov blankets of other things. These edges between things could be where disaster strikes, but on the whole some form of homoeostasis and autopoiesis emerges, whereby the treeness becomes part of a system that both includes it and other things, helping itself to keep regulating all its internal systems, whilst also forming part of other regulation systems. For example the acorn may help the squirrel survive or the tree's root system may help aerate the soil.

An amoeba enclosed within a membrane.

A membrane is a selective barrier; it allows some things to pass through but stops others.

Why might this idea, that all self-organizing systems need to be surrounded by Markov blankets, be the case? I think it is about the relationship between independence and interdependence. We constantly update our decision making based on past experience and current change. We do this in order to survive or to achieve homoeostasis, but so does an amoeba. We exist like the amoeba in the midst of dynamical changing systems all of which are mediated by certain forces. If these systems are to work together, rather than simply break each other apart, they need to be able to ‘couple’ with each other, in order to create ‘interdependences’. If independence is to be maintained alongside interdependence, then these independencies will need to induce Markov blankets, so that the internal, independent state can be statistically separated from the external state. This enables the minimization of the disturbance of free energy, because the internal states (and their blankets) will engage in active Bayesian inference. I.e. that surrounding area where the tree engages with soil, squirrel and rain is an area of probed uncertainty, whereby updates in decision making based on past experience and current change are made all the time in order to ensure the continuing existence of the core independence, which is also reliant on the continuing existence of the surrounding systems that it finds itself nested within. This process can be statistically modelled and when it is, points are used and not lines.

We can now get back to drawing again and in particular the issue of collaboration. Perhaps you now have an idea of where all my ramblings are going, I am trying to articulate something about the way artists have to negotiate with each other’s drawings, and that the process is not that dissimilar to the way all life forms have to negotiate with their ever changing environment if they are to survive.

Every drawing begins with a dot... the tip of a brush, the point of a pencil, the sharp edge of a broken stick of charcoal or the nib of a pen, touches a sheet of paper, the dot, that material manifestation of the point, becomes the centre out of which will grow more dots, lines and forms, all of which emerge from that initial point. This is the opposite of the point in Euclid.

The universe as star dots

The point is formed by the coming together of axes of directionality but the dot is the centre from which all forms emerge, it is the cosmic mother of invention. The first imaginative drawing was done in the mind and not scratched into sand or drawn on a cave wall.

The first drawing would have emerged from the field of dots seen in the sky at night, like the Great Bear of astrology / astronomy, it would have consisted of a series of dots that were in someone's mind's eye morphing into forms that emerged from tales of Gods and Goddesses. Dots collaborate with each other to form new things. A broken or dotted line is permeable, it forms a boundary that can be crossed rather than a fence to keep things out.

A dot doesn’t have to be perfectly round, it can have directionality, it can pulse with life.

Van Gogh

When Van Gogh draws or Monet paints, their marks or brushstrokes are in effect elongated or distorted fields of dots, rather than filled in lines. The post-impressionists perhaps above all recognised the power of the dot, the importance of a field of marks that were never fixed, but which drifted across the surface and plunged the mind into a floating world of perceptual actions.

If artists were to collaborate with the world they had to allow themselves to dissolve into it. The fixed moment of photographic time had just arrived and like lines, photographs froze boundaries and didn’t engage with process only surfaces.

However close on photography’s heels was emerging the technology of the moving image. Initially using drawing to create animations such as in the phenakistiscope and the zoetrope, and then after the pioneering work of Muybridge and others photography itself was allied to movement and as this technology was understood and developed over the next 100 years, it eventually became the norm and the still image was regarded more and more as a technology with severe limitations. However drawing was never really about the frozen moment and its strength was always its ability to simultaneously provide an image for contemplation and provide a surface to unravel. The traces of the maker’s movements captured in the marks and the images made arriving out of the collection of marks as they were developed over a surface.

Second and third stages of a Drawing Dialogue image

The conjunction of traces of body movement and different marks and lines operates as a simultaneity, and this is what makes the images in the exhibition so interesting, and which opens out opportunities for thoughtful reflection every time it happens.

Drawing continues to be done and this exhibition celebrates drawing done as a form of collaboration, each artist beginning each drawing with a point, a dot of intentionality that has at some point to engage with another artist’s field of marks or lines or shapes. The best of these drawings maintain as we do ourselves, a state of homoeostasis, whereby each artist has probed the uncertainty of either a white sheet of paper or the energy fields of other artists’ marks, and engaged in decision making based on their past experience and the new challenge of other artists’ worlds emerging out of the paper. They will partly have to ensure the continuing existence of their core independence, while at the same time allowing the work of others to make total sense, as they build a new world within the one they are nested within. Perhaps this uncertain certainty will open doors, perhaps it will lead to thoughts and imagery unthinkable as solitary endeavours. What is true is that without cooperation and a willingness to soften boundaries and become permeable to other ideas, as people we will become ossified and brittle, easily broken and ripe for being blown away by the winds of change. Collaborative drawing being not just about making weird or strange imagery, but also being a model for survival and a gateway into another world where things are less defined and where words are vowels much more than nouns and where dots are sometimes privileged over lines.

See also: