However I also make ceramics and the ceramics work in a different way to the drawings. I have been looking at quantum theories in relation to thinking again and perhaps I could call the difference between my thoughts existing in the form of being in my mind, or captured in drawings as opposed to ceramics, as them existing in different states. In a similar way to water being able to switch between the states of liquid, ice or steam.

I've been reading 'You are the Universe' by Deepak Chopra and Menas Kafatos, an interesting take on how to think about our relationship with the universe. They posit a universe that is itself conscious and suggest that we can only engage with this universe via our own consciousness, as what is out there is consciousness itself. They use lots of metaphors to make their point, some of which personally rang true. For instance my continuing difficulty with photographs as indicators of reality, was reinforced by their image of a photograph of a surfer riding a wave. They point out that by cutting the surfer and the wave out of the context of events moving through time, we have no idea of the reality of the situation, is the wave moving at 20 miles an hour or 30? Is the surfer about to fall or ride the wave? Time is an essential part of the perception of experience and by cutting an event out of time, we lose an essential aspect of the reality of the situation. However the most interesting aspect for myself was that as all things participate in this consciousness, I could see a clear link between what they were arguing and my own interest in a return to a more animist way of interacting with the world. We are in effect made of the same stuff, or composed in a similar way to everything around us and as such what we think of as consciousness, is actually the way the physical materials that make up the universe operate. So for myself, when I have an idea in my head and I find it hard to grasp what it is, I give it some form of a physical existence as an externalised thought. A thought arising out of my own consciousness, is given another form as it wraps material around itself, and that form is another form or state of consciousness. My perhaps misunderstood reading of 'You are the universe' was that if the observer principle effects whether or not light is seen as a photon particle or a wave, it must be consciousness that determines the particular 'state' that we find these things behaving in. As there is no other way that we can be conscious except as the being we are, we are always in effect creating the world as we see it. As soon as we die, the world disappears.

On a more basic level in relation to my own thinking about how art works, the things I make are extensions or embodiments of my thought as it materialises in conjunction with whatever materials I am using to think with. The particular state of two dimensionality seeming to carry ideas in a way that leaves them more fluid, whilst when made as three dimensional objects the ideas seem more fixed.

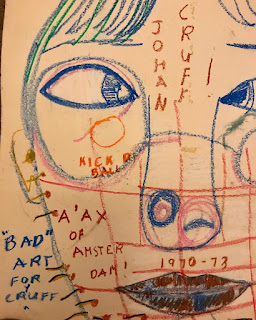

Tranculments are in my mind also linked to what Karl Marx called, 'commodity fetishism', a term he appropriated from a 1760s text, 'The Cult of Fetish Gods' by Charles de Brosses. Marx (1867, p. 42) wrote, "A commodity appears at first sight an extremely obvious, trivial thing. But its analysis brings out that it is a very strange thing, abounding in metaphysical subtleties and theological niceties". Something I might say equally in relation to tranculments. Marx had taken a term that had been used to refer to a belief that spiritual power or life energy can be found in inanimate things, specifically a belief in totems. He understood that a belief that invisible animate powers exist within inanimate objects, was essential to any meaning system that embeds the believer into the wider inanimate world that he or she exists within. Things were Marx believed 'magical', in that they could promise 'magical' effects, that were he would argue 'fictional', but which nevertheless appeared to be the drivers for possible life changing transformations. The tranculments I make are in effect my coinage, like another inanimate thing 'money', they can be used in a form of exchange, but in my case the exchange is in terms of psychic value, rather than monetary value.

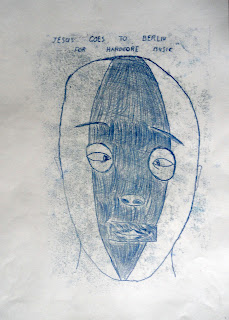

When someone looks at any of these images, I have to hope that some area or aspect of their personal world view might coincide or overlap with mine, if not everything will be met with total incomprehension. In the image above what is within the centre circles overlaps, even though the main interests of the two observers are different. But the two circles don't overlap precisely, something I'm suggesting never happens, so that we never quite communicate exactly what we are getting at, but even so, a fair amount might get through.