Alberto Burri

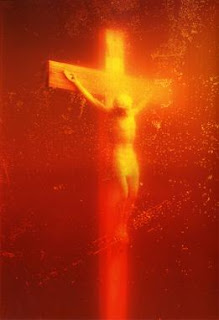

This approach is similar to but not the same as using real blood to create images. Burri is in effect still maintaining a certain distance from the subject. He does not use rags soaked in blood, but uses paint and a surface treatment such as cutting or slicing to evoke wounds. He wants his audience to think about things and is trying to use the drama of material association to frame the idea. Artists such as Hermann Nitsch and Portia Munson (see previous post) want their audience to make a direct visceral connection with the actuality of blood. How artists break through the distancing that visual metaphor creates is an old problem and it is often associated with the difference between looking and touching.

If we go back to the 16th century and look at Caravaggio’s 'Incredulity of St Thomas' I think we can see the root of the problem. Thomas can't believe that this figure he sees before him is Christ, he believed that Christ had been nailed to a cross and was speared; therefore he should be dead. But touch is a more powerful indication of the reality of things than sight, so Christ allows Thomas to put a finger into the wound in Christ's side. Sight is now confirmed by touch and Thomas is finally convinced of the risen Christ's new spiritual reality.

Caravaggio 'The Incredulity of St Thomas'

Margaret Atwood wrote: “Touch comes before sight, before speech. It is the first language and the last, and it always tells the truth.” Atwood points to the fact that authenticity is vital to the conviction of our beliefs and 'things' have a substantial weighty 'reality' that words and images lack and therefore give authenticity.

The linking of looking and touching is an essential element in the moving of an idea like the stain from an intellectual understanding, to a much more visceral 'knowing'.

Traces of reality are left when one thing bumps into another. However traces are incomplete records of events, so they are often ambiguous, but even so we often read traces as signs. A brown stain can be a sign of a recently spilled cup of tea or of the passing of a wounded man. The physical reality of a stain highlights the idea that a drawing can be an object, a thing in the world that acts upon the world and can be acted upon, rather than being an illusion or window onto the world. In this way a stain can be seen as a record of facts after the event. A window onto the world also denotes a certain distancing, and the stain as a factual record again suggests that this is something we can touch as well as see, the 'fact' of life being more important than a reflection on it.

The Turin Shroud is an object / drawing that sits right in the middle of these issues.

The Turin Shroud

The Turin Shroud is one piece of cloth that was at some point folded in half and was used to wrap up a body. However the body's traces were somehow embedded into the cloth. You can just about see the face near the centre fold and once you can see that the rest of the body comes into focus, the top half of the image above carries a back impression of the figure and the bottom half the front. It is easier to see in negative (below).

The reddish-brown stains that are found on the cloth it is argued correlate with the Biblical description of the death of Jesus. The triangular shaped inserts are patches that were sewn into the cloth by Poor Clare nuns in order to repair damage caused when molten silver from an incinerated chalice came into contact with the folded up shroud during a fire in 1532. How old it is uncertain and how authentic it is also questionable, as long ago as1390 Bishop Pierre d'Arcis wrote a memorandum to antipope Clement VII stating that the shroud was a forgery and that an artist had confessed to its making.

The authenticity of the shroud has been at the centre of several forensic investigations, some concentrating on the materials used to make the image and others on the weave and consistency of the linen itself. The fact that the image of a man is of both the back and front has suggested to many people that the image it an actual print taken directly from a person and that this person may have had a fever that caused them to sweat extensively and thus stain the shroud in their image. Others have argued that the image is too like how someone would be seen rather than an imprint of the linen touching someone. Therefore it is argued the image is in some way 'painted' or impressed into the linen by an artist. What is interesting to me is that the more the image is seen to be the result of touch or direct contact it is authentic and the more it is seen to be the result of an artist making an image it is seen as a 'fake'. The stains in this case hovering between being symbols of Christian veneration and human artifice. Are these brown stains the blood of Christ (haemoglobin) or simply the result of iron oxide based pigments?

Iron oxide is of course also known as rust and if you leave a rusty object on damp paper or wrap it in cloth you will be able to make an impression. Rust stains are a common problem when clothes are left out to dry and inadvertently find themselves in contact with some old rusting iron. Some rusted objects are more associative than others. In certain situations scissors can be weapons. Superficially rust stains can look like scorching, both are usually brown but they have very different associations.

A scorch mark left by a hot iron

In this case we have something that can look like a stain but isn't and as we explore the difference we begin to see how a different set of meanings opens up. A scorch mark is much more a result of violent action. (Think of the holes in the Turin Shroud that required patching or repairing). We brand animals by scorching them and indeed we use hot irons to torture each other.

A tortured victim's iron burn

We seem to have come a long way from Burri's attempt to use red paint and distressed textile surfaces to signify his experiences of bandaging soldiers during war. The last thing I am suggesting is that as artists you need to be more directly engaged with violence in order to depict it. What I am trying to suggest is that the relationship between touch and sight is an important one when it comes to certain types of mark making. Staining in particular has a series of associations that begin to open out if we look at some synonyms.

To stain: to blemish, to soil, to sully, to spoil, to defile, to taint, to besmirch, to discredit.

Whereas the physical traces of something can mean: to hint, to indicate, to point to, to tell, to warn, to leave

evidence or to notify. All of these inferences suggesting that a trace is only a partial indication of something, an incomplete account, which leads to a certain ambiguity. There is no ambiguity in the torture victim's iron burn, we are clear as to the intention of the perpetrators. The fact that whoever did this is not thankfully an artist is important. We might worry about the fact that our ideas are not clear enough or not 'getting through' to our audience. But part of the wonder of communication is that it can be very subtle and still work. You just have to be attentive.

Consider the tale of 'Clever Hans'.

Clever Hans

The horse Clever Hans was a mathematical sensation and he hit headlines during the first decade of the 20th century. If you gave Hans a basic addition or subtraction problem he would nearly always get the answer right by tapping out the answer with his hoof. No one could work out how Hans did it, because when his owner died the horse was still able to perform these feats of counting. Eventually someone solved the problem, Hans was clever but not as a mathematician, but as a reader of human emotions. Hans could sense the growing tension of people around him when he 'counted'. As he neared the right number, Hans would gradually slow down his hoof beats, tension mounted in his audience and this would enable him to respond to the release of emotion as he reached the right answer. Hans was using a high level of emotional intelligence and keen observational skills to communicate with his not quite as sharp human friends.

Sometimes though we need some other information, because traces are as we have seen incomplete evidence. So consider these coffee cup stains below.

These stains were left over from a meeting between a group of people that were having to make a very important decision. The meeting as we can see went on for some time and several cups of coffee were drunk, someone in particular had slopped their coffee into a saucer, probably due to their agitation in relation to the meeting's agenda and as they put their cup down several times, they were inadvertently beginning to create the beginnings of a pattern. How does this 'drawing' communicate? Can we like Sherlock Holmes decipher this image by using inductive reasoning? Do we intuitively read the image as a sign for both a meeting and a long mulling over of an idea? Context and story line are both important here and it is hard to avoid certain narratives even when they are the wrong ones. Everybody thought that Clever Hans was doing what he did as part of some elaborate con trick, therefore the narrative of trying to reveal the trick became so dominant that everyone missed the reality of what Hans was doing. In this case if I told you that this image of coffee cup stains was a detail from a much larger photograph taken in 1942 at the Los Alamos National Laboratory

immediately

after a meeting between General Lesley

Groves, Major John Dudley and J. Robert Oppenheimer, would it change the way you were thinking about the image?

See also: