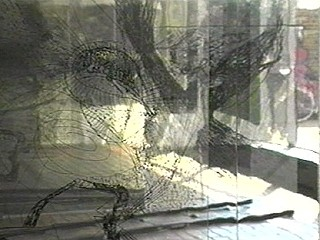

Detail of an imaginary landscape

I was reminded of these quotes when I was listening to Kirsty Young's podcast 'Young Again' that was focused on an interview with the writer Phillip Pullman. He was he said at one time a middle school teacher and during the years 9 to 13 he saw children change their behaviours as they became self aware. He referenced in relation to this, 'On the Marionette Theatre' by Heinrich von Kleist, and this extract below is what I think he was referring to.

"About three years ago", I said, "I was at the baths with a young man who was then remarkably graceful. He was about fifteen, and only faintly could one see the first traces of vanity, a product of the favours shown him by women. It happened that we had recently seen in Paris the figure of the boy pulling a thorn out of his foot. The cast of the statue is well known; you see it in most German collections. My friend looked into a tall mirror just as he was lifting his foot to a stool to dry it, and he was reminded of the statue. He smiled and told me of his discovery. As a matter of fact, I'd noticed it too, at the same moment, but... I don't know if it was to test the quality of his apparent grace or to provide a salutary counter to his vanity... I laughed and said he must be imagining things. He blushed. He lifted his foot a second time, to show me, but the effort was a failure, as anybody could have foreseen. He tried it again a third time, a fourth time, he must have lifted his foot ten times, but it was in vain. He was quite unable to reproduce the same movement. What am I saying? The movements he made were so comical that I was hard put to it not to laugh.

From that day, from that very moment, an extraordinary change came over this boy. He began to spend whole days before the mirror. His attractions slipped away from him, one after the other. An invisible and incomprehensible power seemed to settle like a steel net over the free play of his gestures. A year later nothing remained of the lovely grace which had given pleasure to all who looked at him. I can tell you of a man, still alive, who was a witness to this strange and unfortunate event. He can confirm it, word for word, just as I've described it."

A key moment in Jewish and Christian religious terms was of course the fall of mankind. By eating from the tree of knowledge of good and evil, we were no longer innocent and knowledge brought with it the difficulties and vicissitudes of too much awareness; suddenly we realised we were naked. As knowledge is gained innocence is lost and we become more self-conscious. We have hopefully when children all at some point in our lives inhabited those states of unselfconsciousness; experiences that were often pure and joyful. As adults though we have to attain those types of experiences in other ways. The poet Lorca suggested that we could regain the poetry of unselfconsciousness via what he called 'el duende'; that quality of human 'lost in the moment' action that he found in the best flamenco dancers; who could attain an almost trance like state that made the experience of their dance unforgettable. Lorca believed duende could be found in all the arts, not just in dance, and that it could only come into existence when someone is totally possessed by the experience, one where subject and object are conjoined, where the physical world and the artist merge with the spirit world; and when this happens forms arrive as if “shaped like wind on sand”. (Lorca, in Berger, 2016, p.99) But to achieve that state, we need to practice and practice and practice, until our body/minds meld into one and we know what to do without thinking. As we get older, what we loose in spontaneity we can regain through hard work. Through practice, a new type of grace can be attained that is even better than the one we had as an unselfconscious child. Hard work and long effort can lead eventually to an apparent child like simplicity, which is the state I'm sure Picasso was referring to when he said it takes a lifetime to paint like a child.

Philip Pullman then went on to say that you don't make art because you are inspired, inspiration he stated is a reward for hard work. I have spent endless hours drawing, years and years of making artwork, and gradually I think I'm beginning to make some things that look easy, but which on second looking it hopefully becomes apparent that they have a deep complex conviction behind them.

Childhood is though always with us. I remember at the age of 10 looking out of the window of my bedroom in our house in Himley Road, Dudley. We were about to move house and I wanted to remember the landscape that I had spent so many hours playing in. My bedroom was at the back of the house, it looked out over the scarred wasteland that had been the space within which I had grown into my own self awareness. There was the slag heap down whose sides I used to run or ride my battered old scooter, bomb craters that I had in the past lined their edges with hedge clippings in order to make dens and hide away from everyone else. I looked at the walls that formed the backs of yards where the pigs were kept, animals that would inhabit my imagination throughout my life, a slag mound hillock on which I once stood holding a roof slate in my hand for an older boy to shoot at with his air rifle, the pain as the pellet went into my hand still remembered, the rusty remains of old factory equipment still left broken after wartime bombing, but which were now entangled in weeds; all a backdrop for vivid imaginary play.

That landscape is still with me now, the cradle of my innocence. I have tried to rediscover it time and time again, each time looking for a way of capturing something of that feeling of total immersion that comes from being lost in play. Part of an artist's role it would seem to me is to try to maintain some sort of naivety and to try and hold off the sophistication of adulthood for as long as you can, or at least to fold into the knowledge that comes with age, a memory of the innocence that came first.

The drawing 'Landscape of the Past' is based on my memories of the time when I looked out of that bedroom window. I made the drawing about 5 or 6 years ago, so roughly 60 years after the actual experience. Has enough work been done to regain an innocent eye? I suppose that is up to others to decide, but within my own aesthetic process, the loss of innocence and its rediscovery are key components that need to be added into a mix of animist practices and a need to be entwined into the world and not to stand outside of it. I still struggle to accept the subjective insides that have become enfolded into me from a previous outside, but in that very struggle, perhaps my most interesting work is done.

The drawing 'Running with low cloud and pig' melds together several stories. Clouds were wonderful things to watch as a boy, I would lie on my back for what seemed hours just gazing at them and imagining worlds and creatures they contained. Then one day as a teenager I saw the film based on Michelangelo's life, 'The Agony and the Ecstasy' and saw Charlton Heston doing the same thing, but this time seeing in his clouds the Sistine Chapel Ceiling. This very romantic take on an artist's life effected me deeply and it was one of those 'moments of epiphany', whereby I realised that I wanted to be an artist. The clouds are tadpoles waiting to metamorphose into whatever they needed to. I run down the hill towards home, arms outstretched as I did as a boy, always about to take off, always about to fly. The pig, my nemesis, waits in ambush, all tales from a younger self, but now re-seen with an older eye.

That landscape is still with me now, the cradle of my innocence. I have tried to rediscover it time and time again, each time looking for a way of capturing something of that feeling of total immersion that comes from being lost in play. Part of an artist's role it would seem to me is to try to maintain some sort of naivety and to try and hold off the sophistication of adulthood for as long as you can, or at least to fold into the knowledge that comes with age, a memory of the innocence that came first.

Landscape of the past

The drawing 'Landscape of the Past' is based on my memories of the time when I looked out of that bedroom window. I made the drawing about 5 or 6 years ago, so roughly 60 years after the actual experience. Has enough work been done to regain an innocent eye? I suppose that is up to others to decide, but within my own aesthetic process, the loss of innocence and its rediscovery are key components that need to be added into a mix of animist practices and a need to be entwined into the world and not to stand outside of it. I still struggle to accept the subjective insides that have become enfolded into me from a previous outside, but in that very struggle, perhaps my most interesting work is done.

See also: