Claudette Johnson: Woman with earring Collection of Lubaina Himid

I went over to Rochdale recently to see the Touchstones gallery exhibition, 'A Tall Order'. This was one of the best exhibitions I have seen recently and it reminded me of how important and vital a gallery's curatorial policy can be to the continuing purpose and belief of both art practitioners and the various publics that follow contemporary art. Rochdale Art Gallery under the curatorial steerage of Jill Morgan in the 1980s held some seminal exhibitions and was showcasing the work of artists whose work still resonates today. In fact many of the problems that were raising their heads in society then have continued to confront us and I thought the exhibitions revisited could have been held this year and would still be pertinent. In a letter dated 16th of March 1987 Jill Morgan the then Exhibition Officer stated; “Our policy is to encourage new audiences for art, particularly women, black communities, young people, those with disabilities, and to encourage cultural activity for working class communities. Broadly, to change the domination of art by a white middle class male audience and producer. A tall order!”The focus on exhibiting artists engaged in critical and socio-political practice both gave a platform to those who were not being offered the opportunity to show their work in other high profile publicly funded institutions and provided a focus around which local issues could be reframed within wider national debates.

The recent attempt by many of our art galleries to readdress their holdings and former curatorial stances in recognition of previous bias seems so tardy in relation to what was going on in Rochdale in the 1980s. Forty years ago a public art gallery was addressing these issues and the then curatorial team were proving that if you have vision and commitment you can make a difference.

I was particularly fascinated to see how the exhibition had been curated because I was very aware that Dr Derek Horton, a Leeds based curator had been involved. Back in the 1990s Jill Morgan came to Leeds and it was also the time I was studying for my MA in art and design, something I did at Leeds Metropolitan University which was where both Jill Morgan and Derek Horton were then teaching. I have mentioned Jill in a past post, citing the time when she asked the question, 'why is a painting seen as more important than a jar of home made jam?' It was those sorts of questions that opened people's eyes to the snobbery and elitism of the art world. People have always been happy to put their cakes and jams into local competitions whereby their efforts are judged and compared by other local people who have been entrusted to be fair and robust in their judgements of taste and structure, as well as of colour, texture and smell. Are these not aesthetic qualities and yet these types of activities are excluded from art galleries. Just as the best marrow, onions and potatoes are exhibited and judged in gardening competitions in church halls and local community centres up and down the country, but never in art galleries. Jill's question has still not been answered. Instead the elitist art world has maintained its grip and it could be argued that what it has done is to teach those who were outsiders how to make art that now makes them insiders. Where are all the tattoo artists, the flower arrangers, the finger nail painters, the henna artists, the graffiti writers, the cake decorators, the knitters, the wood veneer artists and all the other people who make aesthetic judgements and use high levels of craft skill in the making of their work?

I also picked up a Harry Meadley brochure while I was there. Harry is another Leeds based artist and who has both Leeds College of Art and Leeds Metropolitan University associations. At one point he managed to negotiate the turning of the gallery spaces of Touchstones over to the people of Rochdale. Following a public call-out to schools, community groups, artists and everybody else, a programme of family events, crafts, film, wellbeing and art was devised where the boundaries between audience, artist, participant or performer were purposefully broken down, so that people could rethink what a gallery space was for. He had previously managed to get the gallery to try and show all their normally hidden holdings. His work 'But what if we tried?' being a provocation that only a gallery like Touchstones would respond to, and they took up his challenge to show everything in their archives. What is of course interesting about both Jill's question and Harry's provocations is that both of them I firmly believe, still advocate 'art' as something purposeful and life enhancing but question its formulation as an elitist occupation. The process of indoctrination into art thinking is still one I remember well. As someone who used to make small images of the steelworks while on night shifts, images that were appreciated by my fellow workers, as someone who then got into an art school in order to undertake a pre-diploma and found his whole summer's hard work of drawing as accurately as he could was held up to ridicule as being devoid of any 'proper' understanding of what drawing was about. As someone that on entering the next level of art education which was the DipAD, went out and found a disused open air lido, with much potential for image making, and then working hard to make those images, was told his work was old fashioned and that it was of no consequence and that what he should be doing was reading Clement Greenberg and making flatness an issue. Gradually I learnt the rules of the game and by my third year I was making work that pre-figured Sherrie Levine's appropriation games by several years; remaking Duchamp's 'Bottlerack' by hand, an art gesture that finally allowed me to make something hand crafted that was also seen as 'clever' and therefore worthy of praise. On leaving art college it took me several years to reboot as someone who loved drawing and who still wanted to make images that related to everyday life. But I now knew the 'tricks of the trade' and could position my work in ways that the art business found acceptable. But in that positioning I knew I was excluding my old steelwork admirers, my family and many of my oldest friends. The ideas I was being introduced to were of course also wonderful, but they could have been introduced in a very different way. Instead of dismissing my previous experiences and ways of understanding the world, they could have been introduced as also being of significance. The fact that as a young man I was prepared to spend a lot of time crafting something was ignored, but that crafting was both a celebration of labour and a love of materials. Perhaps looking back that love was suffocating the material rather than releasing it to be what it could be, but even so the making began with love and care, attributes that I still think are central to how we build our relationships with the wider world.

So what am I saying here? I'm not saying that art has no value. I'm also not saying art cant be evaluated. What I am questioning is who controls the value system, who decides what is good and what is unworthy of attention? These are questions the exhibition in Rochdale asks and which have obviously caused me to reflect on them too. The fact that so much of the work is good is a tribute to the curatorial skills of Dr Derek Horton and his fellow curator Dr Alice Correia. Carefully threaded around a developing narrative, the curatorial team obviously knew their subject very well and were able to source images that both exemplified what was happening and that still had traction for today.

There are several drawings in this exhibition, but also painting, photography, video and three dimensional work. In terms of drawing, I was reminded of how powerful the work of Sonia Boyce, Sutapa Biswas and Lubaina Himid was at the time, but I was also reminded that Steve Bell's drawings for the Guardian were an essential other voice and that Paul Butler was making drawings using traditional techniques that seemed to be at the same time very pertinent to what it felt like to be alive in the 1980s.

The exhibition closes on Saturday, and if you have a chance to get there, do go.

I have a few images taken on my mobile while I was there. Every image behind glass also therefore reflects its environment. As this exhibition was as much about the gallery and its history as the work, perhaps for once these reflective images were appropriate. So bear with some of the crazy reflective images and try to look behind the glass.

Sonia Boyce, She Ain’t Holding Them Up, She’s Holding On (Some English Rose), 1986

Sonia Boyce

Sarah-Joy Ford

Stephen Willats

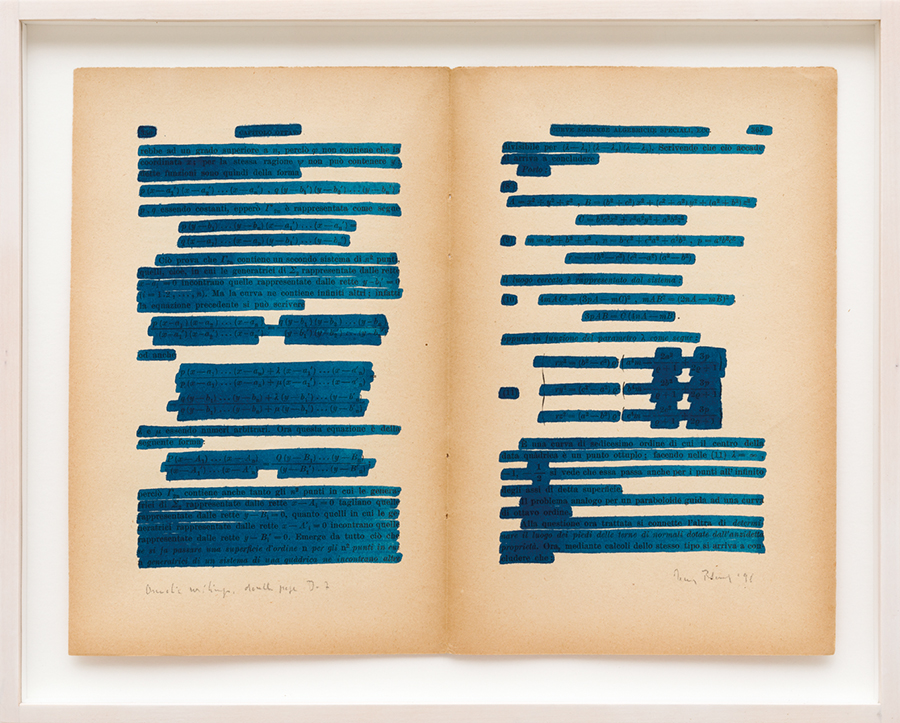

Paul Butler

Sutapa Biswas

Glenys Johnson

Lesley Sanderson

Chila Kumari Burman

Benjamin Slinger

Lubaina HimidCoda

When returning to Leeds I had to wait a while on the platform at Rochdale station. As usual when left to my own devices, I made a drawing to pass the time. What took my eye was the juxtaposition of very different architectural styles, in particular I became fascinated with how the domed building, which I later found out was a Catholic Church dedicated to John the Baptist, was set against a typical example of contemporary modernism. I could see another metaphor emerging, but perhaps a far too easy one. Inside the church there are some beautiful mosaics, and you can look at them on line. See

View from the platform Rochdale station

See also:

Feldman's model of art criticism

Drawing and politics

Drawing as a vehicle for sexual politics

Drawings on show at Leeds City Art Gallery