There is an area of drawing that is often underrated and as I have remarked before, also made to feel inferior by being regarded as illustration. This is drawing done directly in front of the world, reportage, or direct responses to life as it is experienced. Historically this thread includes Pieter Bruegel, Goya, Rembrandt, Otto Dix, Daumier, Edgar Degas and many more artists that at their core looked at and experienced the world through drawing, and in doing so derived a deep understanding of what it is to be human.

I try to continue in my own small way this tradition by walking my local streets and drawing. My skills are nowhere as good as they need to be but at least I feel that some of the reality of the streets seeps into the work I do.

This post is about artists who have drawn directly from experience, and like Goya, sometimes these artists find themselves in dangerous and difficult places, and yet also like Goya and Otto Dix, they still managed to get down on paper their feelings and observations. Drawing is not like taking photographs, the split second of the photograph means that you only glance in the direction of what is happening, sometimes not even looking, because you can only point the camera and hope for a good shot. But if you draw you need to look hard and long, thus confronting the situation, taking it in at a much deeper level.

The artist Avigdor Arikha was known for working only in natural light and for producing each of his images in one day. Both of these working methods were due to Arikha’s decision to focus on prioritising the act of observation. He would often give himself limitations within which to work, for instance at one time restricting himself to black and white, a restriction that he imposed upon himself for seven years.

Working within an imposed set of severe conditions was something Arikha would have had to learn from an early age. He survived his early experiences as a boy in a concentration camp during the second world war, because of drawings he made on scraps of paper of images that were direct impressions of the horrors he was experiencing as a camp inmate. On a visit to the camp, delegates of the Red Cross saw some of his drawings and realising the importance of his revelatory images managed to engineer his own and his sister’s escape.

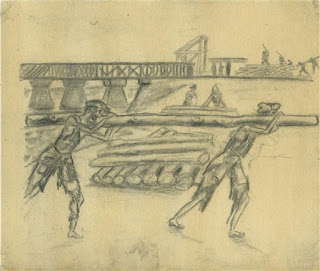

Avigdor Arikha: drawings done as a boy in Transnistria concentration camp

Because of his Jewish identity, Arikha was only able to escape the concentration camp by taking on the identity of a boy who had just died. To become a dead person in order to live is one of those experiences that must shape one's view of life forever and in Arikha's case I think it was seminal to what he was to eventually develop as a body of work. His art training in Israel introduced him to European abstraction and this was to have a lasting impression on his compositional choices; selection and simplification of forms being vital to his own process of self-reflection. His perceptions needed to be stripped down as they arrived in all their complexity in order for him to understand what it was he was seeing. The critic Robert Hughes described Arikha's process as one suffused with an "air of scrupulous anxiety", the act of drawing, being never an easy one, especially when you realise that in some ways you only see through someone else's 'dead' eyes. Arikha's work has a nervous, edgy quality, to it, one that reminds you that no matter how hard one might seek to be objective, a point of view is hard to avoid, because it can seep into the image from the way a pen is held or from the confidence with which a mark is drawn. The artist's 'touch' can at times be just that; a touch that transforms by its very nature.

Lord Home

I well remember Arikha's portrait of Lord Home the Conservative Prime minister, one of those rare portraits that seemed to capture the nature of what the political animal is actually like. Arikha seemed the perfect choice to make a painting of Home, because he was able to see the death in life of the conservative mind.

Avigdor Arikha: Samuel Beckett

Avigdor Arikha: Knife and bread

Avigdor Arikha made many drawings and paintings of people and landscapes, but of all his images the ones that I feel make the most impact are those of simple basic objects. His image above of a knife and bread being a wonderful example of that confrontation with the play of light passing over a few moments of the day. He makes these moments as solid as a mountain, this rock of bread will break your teeth if you try to eat it, it is not for eating it is for looking. This image is of a few moments preserved in all their richness, a sight made all the more precious because at one point there was to be no more looking for Arikha and he still can only see out of a dead boy's eyes.

Eric Taylor: Images drawn in Belsen

The images above are by Eric Taylor, a former principal of the art college in Leeds where I still work. When I began my teaching career Eric was still working in the college making ceramics. He was a quiet, inwardly focused man, who at that time used to come into the college every day to work. This was his reward for services rendered, after devoting his life to art education he was given free access to the college studios and facilities and used these until he was in his 90s. He was a beacon of sanity around which the department rotated, he didn't have to talk, he just made things and made them with love and care and an eye that relied on the experiences of life to tell him what to do. One of those experiences was in the services of His Majesty's Government as a war artist at the end of the second world war. He was one of the artists that had to record what had happened in Belsen concentration camp and there is no way that his training as an artist could have prepared him for what he was asked to document. The drawings he did at the time are now kept in the Imperial War Museum and act as reminders to us all of what people do to people when they forget that all people are people.

Restoring Eric Taylor's mural

Set into the side of the Leeds Arts University's new building, you can see a three part ceramic mosaic mural. It is a joyous celebration of rural life, set into a wall facing a busy city road transport link. This is also the work of Eric Taylor, a far cry from the scenes he was forced to contemplate during his time as a war artist. Now fully restored these colourful murals are passed every day by a new generation of students who have hopefully not had to face what both Avigdor Arikha and Eric Taylor had to experience. However both artists at one time or another had to stare life in the face in order to make their drawings and in that process they learnt both about the world and themselves.

In many ways the artist Pia Linz's practice is the opposite of these older artists' work. But it is perhaps a much closer reflection on how we as people in what we now call the developed world, experience life today. Because she works from behind a transparent shield, she sees the world through a screen and this, it would seem to me, is the everyday situation for many of us, be this the car windscreen, mobile or a computer screen.

Her 'Box Engravings' have developed from ideas of projection. What is interesting here is that these ideas are in fact rooted in the 15th century and if you go back to very old drawing devices such as Durer's perspective frame, the idea of drawing as a record of what passes in front of a flat screen or grid, can be seen as a constant that has lasted since the invention of perspective.

This is what Durer had to say about how to use his drawing apparatus. “Now draw whatever you wish to paint on the pane of glass. This is very suitable for portraiture-especially for those painters who are not sure of themselves. If you wish to use this method to paint a portrait, let the subject rest his head so that he will not move it until all the needful strokes are completed. ”

You can compare Durer's drawing apparatus with drawing aids used at the beginning of the twentieth century, the following text being taken from an advert for Ablett's glass plane above. "The teacher with the position of his eye fixed by the moveable iron ring, traces with brush and Chinese white the outline of the object, (rod, disk, cube or chair etc), which is placed on a table or the floor on the further side of the glass. The pupils, one by one, look through the ring and see for themselves that the lines traced on the Glass by the teacher, coincide with the outline of the model. Pia Linz develops her three dimensional Box Engravings by always using a fixed standpoint and turning around on her own axis. First, she builds a transparent Perspex box construction that is tailor made in response to her chosen location, for instance it might take the shape of a prominent building that can be seen from the location. Then once it is positioned, she sits inside the transparent Perspex construction and draws with a felt marker onto the inside of the construction what she can see. (Obviously she will have to swivel round as she draws in order to do this). After this activity is completed, she makes the drawing permanent by engraving the lines of the drawing into the Perspex.

In contrast to Durer's perspective frame however, in which the observer places themselves in the same position of the artist, here the observer views the world of the Box Engraving from the outside. The world of Linz's perceptions is always therefore contained within her construction. It is as if Linz's perceptions can never really escape the confines of her own head. The older artists had a confidence that their testimony would be something that was communicable to others, they had no need for complex devices. In Linz's case we feel that she has to provide a framework for her experiences, one that has to conceptually reflect on the research behind her ideas. However her work still operates as a drawn testament to the fact that she too sat out in the street and drew what she saw. It is a document and a form of reportage, but contained in a presentation far more suited to present day exhibition demands, the work sitting clearly within the domain of contemporary fine art practice.

Pia Linz: Box Engravings

See also: