If as artists we are to embrace sustainability we will have to re-examine the practices that we call art. This isn't something new and I have looked in the past at how the word 'art' has changed its meaning over time. The stem 'rt' from the old Indo-European language root meant, 'the dynamic process by which the whole cosmos is being created.' A powerful idea that suggests 'rt' and its successor 'art' are much more to do with being involved with unfolding events than making objects, a concept that celebrates the interconnectedness of everything, rather than something just about painting and drawing. Perhaps our society needs to think again about the way art is used or perhaps we need to revisit a much older tradition. Art under capitalism has become about the exchange value of objects, unfortunately the news media now concentrates on the amount of money that an art work achieves at auction and rarely on how art might be used to add value to society. In 2017 the Wall Street Journal reported that the painting 'Salvator Mundi' by De Vinci had been bought for $450 million by Saudi Culture Minister Prince Badr bin Abdullah. A figure so huge that it is almost impossible to begin thinking about what this means. In a time of war, migration of displaced peoples, global warming and planetary wide instability, somehow the putting of so much money into an art investment seems not just futile but criminal, a sign that something has gone wrong with our idea of value.

So it is perhaps time to look at alternatives, of ways of approaching art in such a way that its relevance to our collective understanding or feeling about the world goes beyond whether or not a drawing or painting is suitable to be shown on a gallery wall.

In connection with my earlier posts on sustainability and the linking in of artists associated with eco-awareness, I'd therefore like to add another strand of practice, and in doing so perhaps open out alternative models that some of you might find useful or at least thought provoking.

The term ARTocracy, a sort of 'how to do it' brand name, was first used by Nuno Sacramento and Claudia Zeiske in their 2010 book of the same title. The book systematically shows how creativity could be applied through a sensitive interconnecting of people, context, processes and outputs, all of which it is argued will need to work together if we are to develop more sustainable communities.

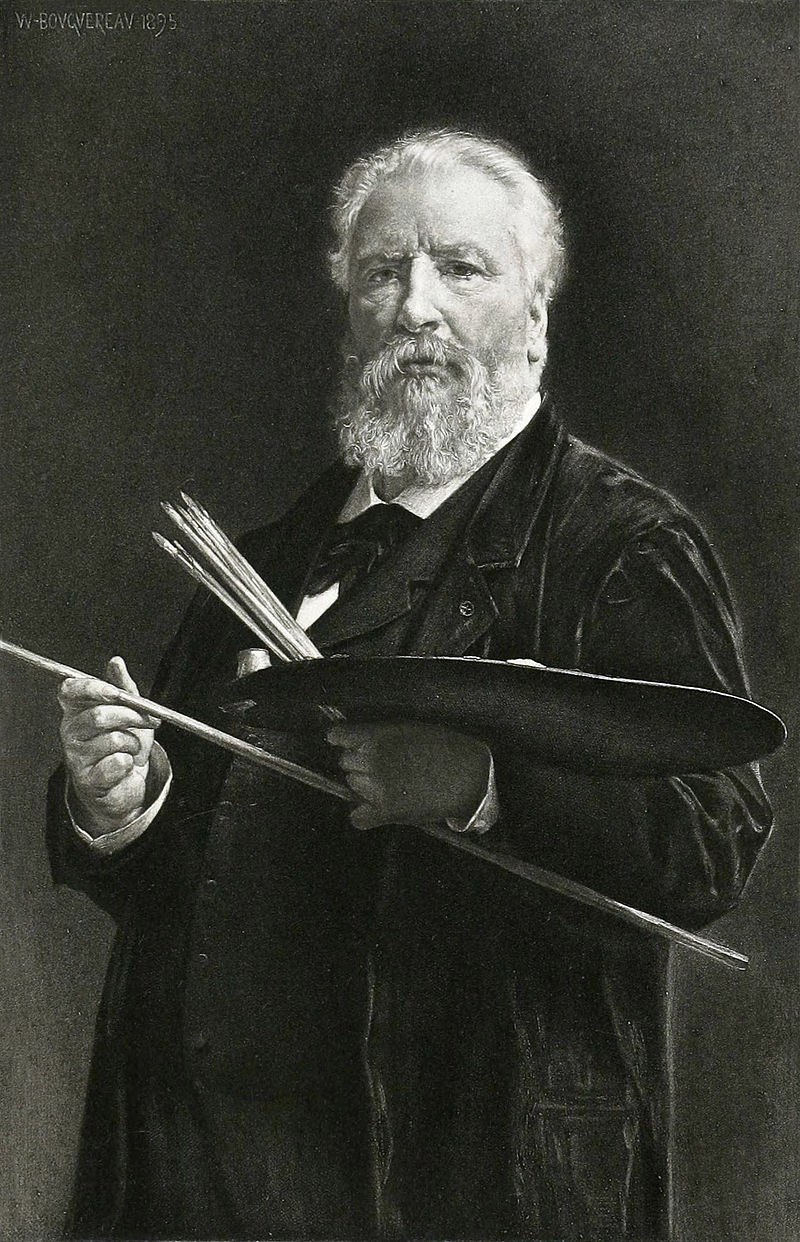

The book is about the organisation of collaborative projects and it is designed to raise awareness as to how projects get off the ground. It provides practical guidance about funding, communication strategies, education and the making of art in community contexts, and in particular it looks at the balance between artistic quality and social consequence. I thought this was interesting because these issues go deep. For instance I remember being told very early on in my career that I was to avoid being didactic. I.e. that I should not intend to teach or give moral instruction through my artwork, if I did my art teacher told me, it would not just be detrimental to its aesthetic value, it could actually stop it being considered as art. Years later I was to meet Joseph Beuys and the first thing he said to me was that he was a teacher and that his artwork was designed to educate and provide a moral framework for others. Beuys used the term 'Social Sculpture' for his work, a term he used to describe an expanded concept of art, in particular to advocate art's potential to transform society. The fact that Beuys was co-founder of the German Green Party, illustrates how deeply he wanted to integrate politics and social awareness into his practice. In 1982, which was the year he was in Leeds; for documenta 7 he proposed to plant 7000 oaks, each one paired with a basalt stone. The 7000 stones were piled up on the lawn in front of the Museum Fridericianum in Kassel with the idea that the pile would shrink every time a tree was planted. The project, seen locally as a gesture towards green urban renewal, took five years to complete and it eventually spread to other cities around the world. If you stand outside the Henry Moore Centre in Leeds and look slightly to your left for an oak tree, you will see one of those Beuys oaks still standing next to its basalt stone.

I thought it useful to begin with ARTocracy simply because it is subtitled; 'Art, Informal Space and Social consequence: A Handbook for socially engaged practice', and we all need to start somewhere and this is a handbook. The first premise it establishes is that the town is the venue. I.e. the place you live is going to be where you develop an audience, find participants, seek content and be a place to both make and present or exhibit work. Your art practice is in effect embedded into the society and particular locality in which you find yourself. This is a very different approach to the idea of the artist as outsider, or cool observer of reality. It also questions the role of the artist as individualist or 'genius', looking at the artist's role as cultural activist, rather than artistic producer, exploring how an artist can energise people and local communities, rather than provide images for contemplation. Art processes it is suggested can be employed to untangle and overcome real-life challenges, defuse conflict, solve problems and open up new possibilities. Sometimes though its good enough just to help people see what's there.

You can read all about it by downloading a pdf from Deveron Arts Projects.

Socially engaged art practice is collaborative and participatory and how you involve people in the work is central to the process. You can involve people and communities in debate, collective action and social interaction. The term 'new genre public art' is another way of thinking about it, a description that was coined by Suzanne Lacy, who wanted to find a way of making public sculpture that wasn't putting up statues of high achievers onto pedestals, as she wanted to show how 'ordinary people' could participate in collective decision making.

What Kind of City? is the title of many of Suzanne Lacy's conversations, she has visited Leeds in the past, and this question was the title of her presentation at the art gallery. Lacy has also engaged directly with drawing in her work. She undertook a collaborative project with the artist Andrea Bowers called appropriately enough; 'Drawing Lessons'. This was a nine-day installation at The Drawing Centre, New York, during which artist Andrea Bowers attempted to teach Lacy to draw. Each day for nine days, Bowers offered Lacy lessons, which were also open to the public. Working together under the scrutiny of the audience, Bowers and Lacy explored the questions, in work and conversation, that they engage with in their individual practices. This really interested me, because I am convinced of the power of conversations as being central to social integration and sensitive action. The project served as a platform for extended conversations with curators, union organisers, people who attended from the area and other artists who draw or do performances. The conversations reflected on feminism, performance art, drawing, and socio-political issues of concern to the artists. For example: what are the roles and problems of representation in public art practice? How do artists reconcile activist and field-based practices with the necessities of production for the gallery and museum? What is the relationship between first and second generation Feminism? What is the role of venue, object, and style in the identification and evaluation of art?

The pulling down of the Colston Statue in Bristol last year, raised many issues about the role of both artists and public statues. If the making of statues is problematic, then what can artists do when they work in public? One project I remember in particular that helped me to think about the possibilities for making art-work in this area was, 'Where The Heart Is' by Graham Fagan. As part of his work with the community of Royston in Glasgow, he discovered that the one thing most people enjoyed or could appreciate was gardening and in particular many people liked roses. Fagan purchased a new rose that had no name, originally known only by a code, JC30518/A. It was named through a consultative process across the entire area of Royston. A pupil from St Roch's Primary School eventually selecting the winning name. Cuttings of the rose were then given to any local people that wanted one and its lovely pink blossom and fragrant scent was the following year to be seen throughout the area.

Eliasson is interested in the connection between an experience that might take place in a gallery and the way it might affect your behaviour when you leave that gallery. Olafur Eliasson is an artist who also uses design skills to solve projects, which again highlights the artificial divide between the two disciplines. His team at Studio Olafur Eliasson consists of craftsmen and specialised technicians, architects, archivists, art historians, web and graphic designers, film-makers, cooks, and administrators. Eliasson and the studio also work with structural engineers and other specialists and collaborate worldwide with cultural practitioners, policymakers, and scientists. His climate change activism has inspired many and his approach suggests that as an artist you can both make things and be engaged in community activism. He is able to make art from the poetics of a situation, as well as from an understanding of the ecological condition of it, as well as from the constraints of physical materials and the possibilities that they offer.

Reyes puts it like this:

Wittengstein stated that if we were to imagine a book which contained only the truth it would have to be entirely composed with jokes. I think in jokes you are led to the truth so quickly that the only way to handle the shock is laughing. Not all jokes produce laughing, there are also slow-smiling jokes, visual puzzles and graphic puns, some jokes are diagrams.

You may remember this one...

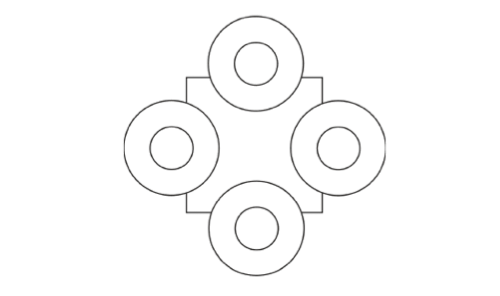

The design process in architecture is concerned with drawing the object, but we often lack tools to draw the social interplay. How do you map individual actors? How do you represent collective entities? This figure below for instance...

I drew this diagram of a collective sombrero and it became the blueprint for a sculpture. It was one of my early participatory sculptures. I took it to different plazas in Mexico city and asked people to wear it. What happens is very curious, for me it represents a paradox of democracy, the huddle has to deliberate endlessly where to go, and they have to walk very slowly not to stumble.

See also:

The Royston Road ProjectReflections on The Colston Statue

Sustainability Resources

Cheap materials

Sustainability 1

Sustainability 2

Drawing and the 12 Principles of Permaculture

Pollution, art and making pigments

Drawing and politics

Object orientated ontology

Art eco awareness and OOO