Jasper Johns: Ink on Plastic

You can of course also use it to make drawings on, just think of it another surface to respond to. However it comes into its own when you have some form of light coming through from the back. Jasper Johns simply uses very white paper behind his ink drawings on plastic film, this being enough to reveal the rich textual possibilities.

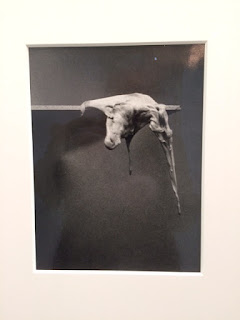

Jasper Johns: 'Regrets' ink on plastic

If you look closely at the image above you can see the way that dilute ink coagulates and has a tendency to thicken and thin in unpredictable ways, thus keeping the surface active and ensuring that what could become 'empty' shapes always have a textual energy about them.

Of course you can also use these transparent sheets of plastic to trace images through and Johns has availed himself of this possibility with his tracings of Cezanne's 'Bathers'.

Jasper Johns: Tracing of Cezanne

The use of brown ink is suggestive of a historical mode and once again the ink's tendency to clot and blob has been used to help transform what could easily have been an uneventful tracing into an image that now sits easily within Johns' concern with the status of the surface and its problematic relationship with the image.

The artist Hadi Tabatabai has used acrylic polyester sheets in a totally different way, relying on the thickness of the sheets to give a sense of depth to his very tightly controlled non figurative constructions.

Hadi Tabatabai

Jim Dine: Charcoal on mylar transparent sheet

Jim Dine had a rich drawing centred practice and at one time he focused directly on making what he called heliogravure prints, which were made directly from drawings made on different transparent surfaces. He used three different categories of supports: clear plastic sheets, frosted plastic sheets, and translucent paper. The Morgan Museum has a very good account of this and their blog post on Dine includes some excellent close-ups of his techniques here. Dine would scratch into the surface, fix the bits of rubbed out charcoal onto the surface with acrylic spray, wipe surfaces down with cloths etc. Anything to get the required effect.

Because these transparent surfaces have a direct association with printmaking, working on them can be a very good way of bridging the gap between the two disciplines. There is a very large light box at the back of the drawing studio and it is often underused, why not get some polyester film and just work up some of your drawings onto it, and then take the most interesting ones along to the print room and see how they translate into silkscreen prints.

You can find out more about 'Truegrain' here It is about £16 a sheet, which might seem expensive, but when compared to canvas and the need to make stretchers it might not seem too bad.

See also:

Monoprinting

Monoprints and lithographs

Drawing and printmaking More on Jasper Johns

More on Jim Dine

SKETCH

See also:

Monoprinting

Monoprints and lithographs

Drawing and printmaking More on Jasper Johns

More on Jim Dine

SKETCH