A frame around a drawing or print in effect creates a window through

which we look. However when looking at vignettes; the edge of the image is more

like a meeting between the land and the sea and this creates an altogether

different sensation. It feels as if the image is much more self-contained; it

unpicks its form out of the very paper it sits on. What do I mean by this? In a

vignette the paper is of course carrying the drawing or print as it would do in

any other case, however because the edges of the image are defined by the

artist’s choice of certain forms, (the texture of leaves at the top of a tree

or some lines representing water), these forms are the boundary or edge of the vignette

world. Because this boundary is a broken edge, the paper appears to integrate

totally into the image, it is as if the image is like a landmass in a map set

into a sea of paper. The rivers of the landmass eventually become the sea, in a

vignette’s case the white in the image, eventually becomes the white of the

paper.

I realise this is always the case in both drawings and prints, the white

is the paper surface, but in a vignette this seems to be so much more clear.

I first came across Tom Lubbock writing about this in a collection of

his writings on drawings, ‘English Graphic’.

He writes, “A framed image depicts a section of the world…it extends

indefinitely off picture. Not so the vignette…Its image is a contained

environment like a desert island or a snow dome.”

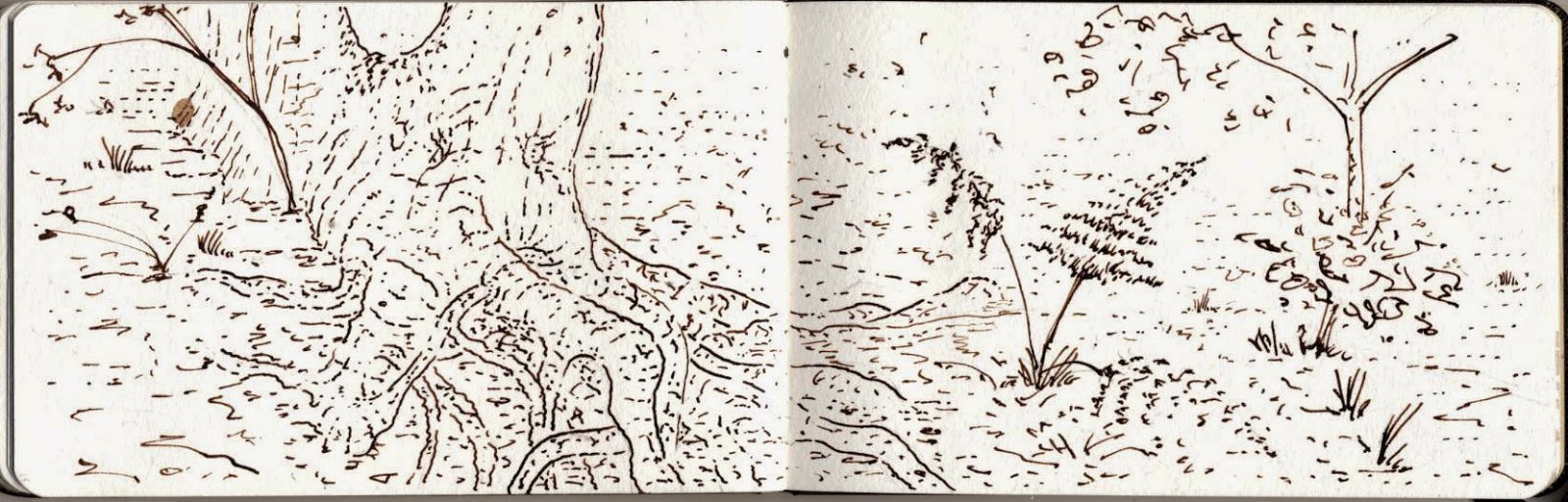

I think this image below by the great English vignette specialist Thomas

Bewick perfectly sums up what Lubbock was talking about.

Thomas Bewick

In this miniature world the trees frame and cut the image out from what

would be sky, the lines of water abruptly stop on the right and the clods of

earth texture define the bottom and left edges. Beyond these edges all is

paper. The man peeing against an old wall is lost in a contemplation of

himself, simultaneously watching his shadow and his own pee, his insides

emptying out and his outsides flattening out. The white of the wall that holds

his shadow is of course the paper on which sits the drawing, it is though a

drawing within a drawing. The man will never stop peeing, his shadow will not

move as the sun goes down, this world is frozen in its own snow dome.

There is an apocryphal myth about the first portrait, it was supposed to

have been a filled in shadow by the Corinthian maid Dibutade, who

outlined her departing lover's shadow on the wall to preserve his image whilst

he was away. The very first drawn figurative images may well have been made this

way.

I seem to have drifted off to the world of the shadow rather than the

vignette, but they are in fact very close relatives. Kara Walker makes much use

of both, the connection being the silhouette.

The edges of the silhouette can be read in a similar way to the edges of the

vignette, my musing on Bewick’s image being in effect that the vignette is like

a cut-out and so is the man’s shadow. Shadows are very powerful and you have to

be quite clear as to how you cast them if they are to be recognizable. This

clarity leads to a powerful simplification of form, therefore an artist working

in this way has to begin to deal with essences.

Kara Walker

A contemporary revisiting of the vignette has been achieved by Kerry James Marshall. His painting series 'Vignettes' demonstrating that older traditions can always be renewed by attaching them to contemporary issues.

As always there is a vast amount of information out there about these

issues.

Some references:

Gromrich, E (1995) Shadows: The Depiction of Cast Shadows in

Western Art London: National Gallery

Stoichita, V (1997) Short history

of the shadow London: Reaktion

Casati, R (2004) Shadows: Unlocking Their Secrets, from Plato

to Our Time London: Vintage

Rutherford, E (2009) Silhouette: The Art of the Shadow New

York: Rizzoli

Lubbock, T (2012) English

Graphic London: Frances Lincoln

Click here for an interview with Victor I. Stoichita the writer of ‘A short history of the shadow’ and click here for more information on the history of the silhouette.

Olly Moss uses laser cut techniques to make his silhouette images

See also: