The more I think about interoception and the world around me, the more I realise that we are shaped by a combination of what lies beneath the surface of our bodies and what lies below the Earth we stand upon. Again it is diagrams that we rely upon to tell us what is there and as I have been having to teach a few sessions on the World Building and Creature Design MA, I have been reminded in particular of how signs of the geological evolution of the Earth and the physiological evolution of our bodies are physically present deep within both.

Perhaps we need to go back to Greek times to see why we can understand things in this way. R. G. Collingwood in his 1945 treatise on the Idea of Nature, had this to say about the Greek view of the natural world;

'Since the world of nature is a world not only of ceaseless motion and therefore alive, but also a world of orderly or regular motion, they accordingly said that the world of nature is not only alive but intelligent; not only a vast animal with a 'soul' or life of its own, but a rational animal with a 'mind' of its own.' (Collingwood, 1960. P. 3)

At one point Collingwood describes Greek thinking on this issue as an analogy. He states that before we know the world we know ourselves and when we look at ourselves we see that a complex series of constantly moving physical parts are kept in equilibrium by a mind directing all the various components. Therefore early philosophers argued that nature as a whole must work the same way. It is intelligent and seeks to maintain autonomy and survive by making decisions that are advantageous to its survival. Interestingly back in 1945 Collingwood was using this argument as a contrast to what he was then calling 'modern' or 'scientific' thought. Concepts such as the embodied mind and ecosophy were yet to enter the world of philosophical academia in England, but Collingwood's description of Greek thought would be very familiar to anyone who has read the Gaia hypothesis. The Gaia concept proposes that living organisms interact with their inorganic surroundings to form synergistic and self-regulating systems that maintain and perpetuate the conditions for life on the planet. Lovelock and Margulis put the idea together in the 1970s, but any believer in animism from two thousand years ago would have also understood the idea. It was the Judeo-Christian concept of a monotheistic God that removed this embodied metaphor, instead it was God the great creator, the engineer that lay behind everything, who was responsible for why things worked in the way they did. This took away nature's autonomy or as God put it:

'Let us make man in our image, after our likeness: and let them have dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the fowl of the air, and over the cattle, and over all the earth, and over every creeping thing that creepeth upon the earth.' Genesis 1:26

Instead of the world being regarded as a giant complex intelligent interconnected physical being, a thing that we had to both commune with and fit in with if we were to survive, we were given the idea that we were in some way better than nature and that we could 'have dominion' over it.

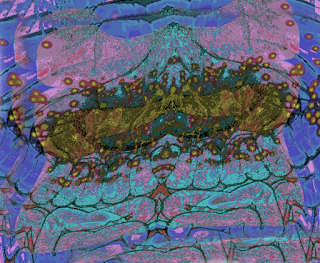

However the ancient idea that the world of nature is not only alive but intelligent and that it is a vast animal with a 'soul' or life of its own, still seems to have traction. Sometimes we use the term 'bodyscape' to describe the metaphorical use of body imagery in relation to landscape. Ancient metaphors that understood the earth to be modelled on the human body are sometimes seen as being one-way relationships; the ‘landscape as body', but more recent changes in philosophical thinking, in particular the material turn and object orientated ontology, point to a two way process, 'the body as landscape' being just as significant.

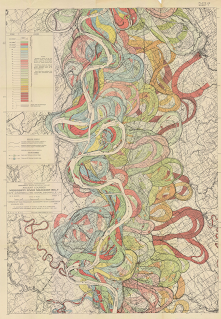

Pioneering stratigrapher William Smith is credited with creating the first useful geological map, (see image at the start of this post), and it is very interesting to compare drawings of slices through human skin to slices through the Earth's mantle. The fact that we think of rocks as having veins suggests that we see the layers of geological strata as being analogous to the way we think about our own bodies.

Visualisations of layers of the skin

In the image above numbers are used to annotate the various different layers as we progress down into the human body. For example '1' is the cuticle and '2' its soft layer. '4' represents the network of nerves and '6' three nerves that divide off from that network. The way the cross section is drawn in many ways brings together various ideas of bodies and landscapes, the need to create distinct textural areas being common to both formats, stippling and broken lines being used by both geologists and anatomists to identify different layers.The two images directly above are from a body mapping workshop led by South African artist Jane Solomon. To create these Body Maps, participants filled a life-sized outline of their bodies with handprints, footprints, personal symbols and text. Ntombizodwa states; "Look here where I have painted the virus. On 19 January 2001 I became very sick. Stomach pains and headache. It was summer time, the season of peach and apricot, and I thought that’s why I had a sore stomach."

The image 'Homme 4D' reminded me of a time when I used to collect old anatomy drawings, in particular ones that opened out and revealed the body as a set of layers. These disappeared many years ago, but I did find this image on a flickr site, which is another example of how to display a body seen through time as well as space, in this case folding out a series of layered representations.

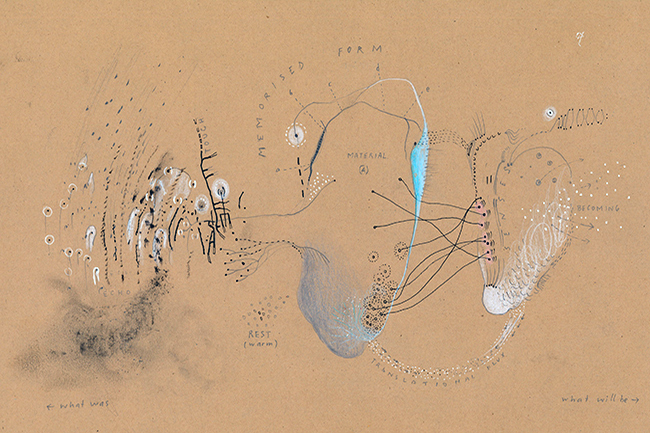

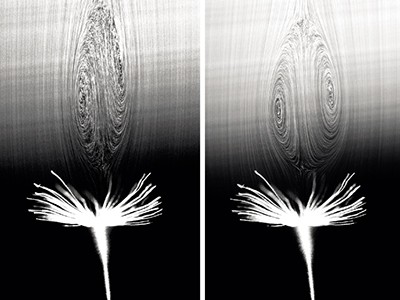

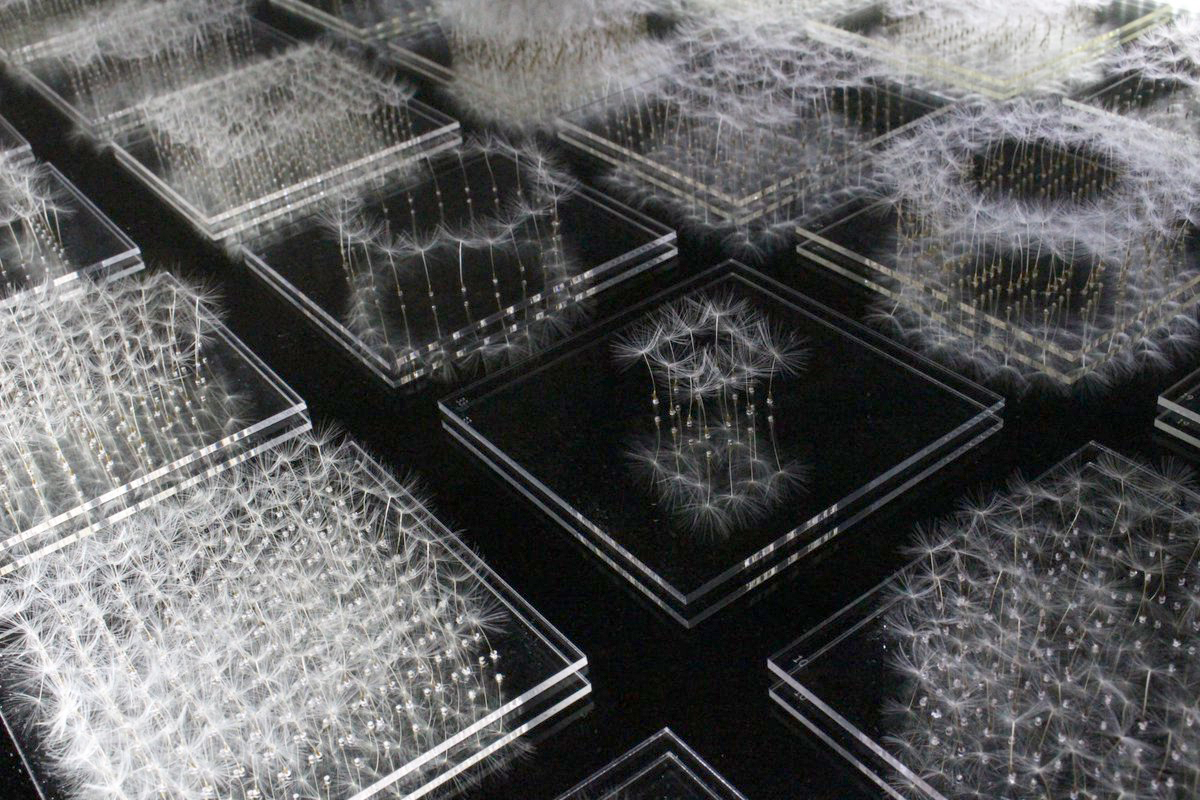

Nikolaus Gansterer's Embodied Diagrams series derive from a four year research project Choreo-graphic Figures: Deviations from the Line. This was a collaborative project that developed shared figures of thought, speech, and movement reflecting on the specific nature of ‘thinking-feeling-knowing’ operative within artistic practices that seek to represent the body. Drawing was used as a translational bodily process that was able to help the research team imagine a variety of forms in which a drawing of the body can become manifest, materialise, and take shape. Gansterer. points out that, 'The German words for drawing (zeichnen) and for notation, recording (aufzeichnen) share the same etymological root'. Acknowledging this, Gansterer produces 'scores' as imaginative prompts. These 'scores' are used to map the complex 'relation-scape' between body, place and atmosphere, a 'diagrammatic (re-)presentation of embodied knowledge(s).'

He describes his images as mapping the durational ‘taking place’ of something happening live and the subtle processes in the event of "figuring something out". This situation intrigued me, because in my own work I had been trying to balance a representation of a thing with a process, for instance an awareness of a pain and at the same time of the process of feeling the pain and of communicating it, a quite difficult process because it crossed several boundaries. The British 'stiff upper lip' might for instance, make it hard to measure pain's effect on a subject taught to show no emotion.

Gansterer worked in collaboration with the writer Emma Cocker, dancer Mariella Greil and others and their work is available at: www.choreo-graphic-figures.net I was particularly fascinated by the collaborative aspects of Gansterer's research and as I have already been working in collaboration myself, think it is perhaps time to revisit some of the issues involved. The fact that mapping is usually associated with geological terrain is something I don't think I've made the most of and as I have been trying to visualise the invisible, mapping might offer a way of building in signposts or guides as to where things might be located.