Sketches for 'Ties'

Wayne Thiebaud: Ties

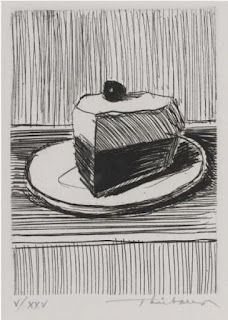

Something as simple as a hanging tie, gave Thiebaud plenty of food for thought, in fact he referred to his compositional sketches as “thinking drawings.” His compositional drawings can also be regarded as art works in their own right; his interest in visual language was always refined and very controlled, as when ordering and organising rhythms of black and white in the image of cake slices below.

If you look at his various drawings of confectionary you can see his control of formal abstract concerns very clearly. The dividing line between the table top and the wall behind is the formal fulcrum around which he organises both images below, an idea that relates to looking that I suspect he took from Cézanne. Look at the ellipse of the plate beneath the cake covered in dripping chocolate sauce; it hits the horizontal behind the cake, it is hidden, but we know it will just touch the line. This touch is a sort of invisible, hidden anchor point. However when you look again, you realise the two sides of the plate are forming slightly different ellipses, the one on the right flattens and takes a slightly different curvature to the one on the left, if this was geometry they would slightly misalign. The shadow of the confectionary falls to the right, and as it does its visual weight does two things. It makes room for itself by pushing the cake and its plate to the left, a simple compositional move, but at the same time the curve of the plate edge is flattened, suggesting that the visual weight of the shadow as it crosses the plate, is also a real weight and it is this weight that is pushing down the ellipse.

If you look at the ellipse of the plate immediately below, once again it wont quite join with the other side of the plate's ellipse, there is a visual rupture and this spatial jump sits within the formal geometry of three rectangles, one identifying a front space and another a back space, whilst the cake sits on and in the rectangle in between. The black cherry, being a sort of focal point around which everything revolves. A classical composition, giving gravitas to a subject that had previously not been seen fit as a worthy subject to paint, an approach that at the time, was also re-vitalising the still-life tradition.

If you look at Cézanne's work you can see a similar set of issues emerging. In Cézanne's drawing of a pear below, you can sense the looking that is going on, as the diagonal from the left moves across the image, it re-emerges to the right of the pear slightly higher. The edges of the pear are often found to be in more than one place. The more you look at this image the more your eyes become accustomed to a sort of scanning and finding mode, one where you need to become more aware of two eyes moving in unison, of a head turning as attention moves to the left and then of a neck rocking that head, as the mind seeks to begin stitching together these various points of view. Points of view taken as the body readjusts itself constantly in order to make sure the eyes have enough information to ascertain the spatial moment that the pear is happening within. This image is a recreation of the time of the looking rather than an image of a pear.

Cézanne

If we look at a more composed image of Cézanne's such as the still-life painting below, what Thiebaud was doing and how much he learnt from Cézanne becomes clearer.

Cézanne

The ellipse of the saucer is broken and bent both by the apple sitting in the space in front of it and by the cup itself as the ellipse passes behind it. Cézanne would have watched himself look at the situation and could then recreate this looking as a formal element within the composition. These points of spatial rupture are where the world of perspective or photographic space falls apart and we enter the world of experienced space. Cézanne was a phenomenologist before phenomenology had become a proper philosophical movement; this is why Merleau-Ponty wrote his seminal paper 'Cézanne's Doubt', as he was very aware that Cézanne was opening our eyes to the moment of seeing, and in doing so, made us all ask questions as to what it is to actually 'see' something.

However Thiebaud is not Cézanne and he has a related but different agenda. Thiebaud is concerned to reactivate memory, but he uses visual tropes taken from Cézanne to do this.

Wayne Thiebaud

If we look at the painting of the slice of tart above, as with the drawings we have already seen, Thiebaud activates the eyes by breaking the ellipse of the plate behind the tart slice. He is also in this case of course drawing in colour. He 'doubles' the edge of his plate, so that the optical buzz of blue against orange replaces the line in more than one place. Colour adds vibration to rhythmic action, shadows have the same intense colour presence as objects and the paint texture reinforces this rhythmic dynamic. This is however a painting done from memory. It is an image of Thiebaud's youth, a time when all the cakes were the best cakes, when mum's apple pie was the bee's knees and all the cake shops had perfectly organised shop displays.

Thiebaud is tapping into the way memory clarifies and sorts out experience. The artist and illustrator Quentin Blake was on TV last week talking about his approach to drawing and he spoke of his time as a young man taking life drawing classes. Blake used to draw in response to the live situation, but then go home and re-draw the figure again from memory. His memory drawings were he stated so much better, because they eliminated all the inessentials and they were now drawings of what the essence of a figure was, or at least what Blake thought of as the boiled down core of the previous experience. These memory drawings helped him to develop a visually centred mind that could tap into a personal lexicon of human forms, a body of visualisations that he still relies on to instinctively emerge and help him find an image as he begins each new drawing.

One problem with memory however is that it can in comparison with a live experience be a little flat, sort of slightly out of focus but Thiebaud overcomes this by reactivating the image with live colour. His control of optical dazzle is very sophisticated, often using shadows as if they are real things, he is able to release his objects into the space they are painted into. The optical 'ping' of these images is phenomenal and Thiebaud could be regarded more as an 'Op' artist, than a 'Pop' artist.

I'm still fascinated by these issues because as a maker of images I believe I have to take into account some of these fundamentals about perception.

Of course Thiebaud didn't just make images about cakes, he took his sketchbooks with him everywhere and the same concerns emerge whether he is painting a cake sitting on a table or trying to compose an image of a road intersection.

Wayne Thiebaud

Thiebaud's work is a reminder of some very basic things. Composition is a powerful tool and you can use drawing to try out variations before embarking on more 'finished' images. He also gives us a way into escaping the tyranny of the photograph and its fixed single point perspective. By working from memory he was able to clarify the complexity of the world and boil it down into images that relived or re-built experiences rather than trying to copy them.

See also:

Richard McGuire's 'Here' A very different approach to dealing with visual memory

No comments:

Post a Comment