False nose: pencil and wax crayon

The drawing above of a false nose was done while I was waiting for someone. I was in a house in Glasgow and for some reason the person who owned the house had this false nose lying on a table near to where I was sitting. I began to doodle something on a piece of yellowish paper, a something you can just about see as a ghost of its former self. Once I had realised I could develop the drawing further, I removed the initial drawing with a white oil pastel. As I realised I had more time than I thought I had, I changed focus, this time trying much harder to establish a more convincing shape for the false nose. I began to realise the drawing could be read in two ways, with the bottom of the nose either open and facing out into the space, or lying flat on the table surface. This flicking between states is fascinating, because it keeps visual possibilities open and alive to constant reinterpretation. I'm always aware of Cezanne when doing drawings like this. He was a master of the small difference in viewpoint. As I drew I was moving my head, so that curves to the left of the image are made from one viewpoint and curves slightly to the right are drawn from another. As a small drawing like this gradually emerges one of the issues is how much do you adjust different aspects of the drawing to allow them to fit together as a whole. This I believe can only be done by instinct. There will be an overall feeling tone that arises, one that makes the difference between the drawing being alive or dead. It is in relation to this feeling tone that the most convincing adjustments are made, not the measuring of relationships. However, is there enough information to make the drawing convincing? Does it tell enough of a story of its making? Is there enough in this drawing to suggest a layered read or double life? Is it experiential as well as metaphorical? In small drawings like this, I can see all sorts of possibilities; a scrap of visual information can provide a thoughtful few moments that at some future time might become a much more worked through idea. I would hope that in changing focus as the drawing was emerging, this has helped to get across an idea of compacted time, of a series of decisions made and captured in such a way that they all continue to operate on the mind of the observer, thus keeping the initial experiences alive. A dialogue with an inanimate object being hopefully as rich as a dialogue with another human being. A stand alone drawing done in the security of someone's kitchen is though very different to a series of drawings done in the open air.

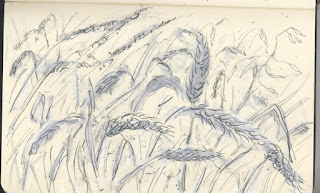

Below are some sketchbook drawings done down in West Wittering of a wheat field. I've drawn this field several times and each time something new occurs to me.

Sketchbook pages

The top drawing is made on a single A5 sketchbook page. It is again made in pencil, and white oil pastel is used in conjunction with the pencil as both an eraser and as a method of giving an extra dimension to both the textural and the tonal range I can make when working in pencil. The paper is creamy white, and is smooth and about 100 gsm in weight. The two drawings below, done on the same day, are made in a small A6 sketchbook, the paper is watercolour weight and the images take advantage of the landscape format that is on offer if you work right across both pages. This time pen, brush and ink is the medium. The metaphors available when drawing a field are very different to those that come to mind when drawing a false nose. A field of wheat is in constant movement, it is more like trying to draw the surface of the sea than an object. Therefore rhythm becomes more important. The pencil drawing felt too stiff, so I moved on to pen and ink because each stroke is much easier to read as an energy container. Close up and more distant views again change the nature of the marks made, the furthest away forms being made simply with a brush and dilute ink. The wind blows as I draw, my feet push into the earth, there is the sound of the outdoors and an awareness of small creatures moving through the landscape and I am like all these things, tied into the world in my own networks of connection, our occurring together in this field at this particular point in time being the result of far too many small and large happenstances for me to articulate, but we are all arriving at the same time, myself, the landscape and the drawing.

It's interesting to compare a drawing of wheat done from a much more scientific point of view, such as the image below.

I'm very aware that my drawings tell the viewer very little about the actual nature of each individual seed head. My eyesight isn't as good as it was, but more importantly I was trying to capture an essence of the experience, something that could replicate the feeling of a dynamic rather than a snapshot of time. The drawing of wheat above is focused on very specific scientific information, the seeds and their various shapes are picked out and arranged next to their respective cereal grasses. In particular they are made to produce information that will be scientifically useful for another human being. My sketchbook drawings it could be argued are far less useful, however they do point to a certain type of relationship a particular human being had at a particular moment in time with a field of wheat and in that very fact, perhaps this is their use value. I was prepared to stop and have some sort of conversation with the field, the drawing being perhaps like some sort of animist language, the spirit of the field now reflected in the spirit of the marks made.

There is a fundamental limitation to the drawings I have been showing as examples of how I have tried to build images of experiences. In particular small drawings can only hold certain sorts of information about time and space. Experiences are durational, often built in relation to overlapping time periods and in relation to very different perceptual viewpoints. My experience of anything will also include memories of previous experiences that help me understand the experience I am having, these memories and new perceptions become locked together to make complex amalgams and the sketchbook drawings shown so far are isolated examples of observational experiences. However they can inform the process and the best of them can hopefully stand scrutiny as examples of drawing as observational thinking. These sketchbook drawings operating like vignettes within a short one act play.

Allegorical map of Chapeltown

The drawing above is a drawing that is more like a novel. I attempted to combine various physical awarenesses of spatial movement with symbols and observations that all at one time or another had a role to play in the understanding of the story/s that weave through an area that I know well. This is a link to another map type drawing one I produced after several conversations with people who had arrived in Leeds after some horrid experiences getting there and who were now living in high rise flats. Brexit, Trump's wall, a fear of the future and of the past, what it was like to arrive on the South Coast of England, stranded fish and several other stories were all entwined in this drawing, one that was struggling to cope with so many issues, but which was at least as far as I was concerned about stuff.

The map is a sort of dreamtime structure, but unlike the real dreamtime, it isn't tied into the culture of the everyday, it sits outside the experiences that contributed to its making and this I would argue is a problem, a problem not just for these two particular drawings, but for the vast majority of Western art as it is produced today.

So how can this dichotomy be resolved? Artists such as Joseph Beuys realised that if their art was to really connect with people it had to work on many levels at once. Drawing, materials thinking, performance, poetry, sound, text, installation, etc., each element supporting other elements and adding to the potential for meaning construction with as wide a range of communication channels as possible. In the far distant past cave painting would have been set into a series of rituals that would have included the intonations of spells, the singing of hymn type chantings, symbolic dancing and stories told, and Beuys was very aware of this. So what am I proposing? First of all and most importantly, I think that drawing is still a very powerful tool and one that allows human beings to have a dialogue with other things that are not other humans. To draw a false plastic nose left on a table is to take it seriously. We humans have spent too many years not taking anything else seriously except ourselves. So if drawing things can help attune us to other things that must be good. Secondly drawing uses materials to make meaning, in doing this the actual activity of making drawings binds us as humans with other materials, this entanglement creates a language, a language which is a symbiosis between human and non-human materials. Again I think this is important, because it reminds us that we can't do things on our own. However we live in a society that is not used to reading drawings, so other communication channels need to be used to help both make others aware of the potential of drawing and more importantly to raise awareness of what is now often called OOO or object orientated ontology. A way of thinking that reminds us of the primacy of things and that tries to rebalance our human tendency to see everything as either an extension of ourselves or as something we can control. Drawing needs to be embedded into the fabric of society and seen as part of a much wider idea, an idea of a society that recognises how the entanglement of everything together means that we have to act respectfully and thoughtfully in relation to animals, objects, processes and other people.

Some links to other posts that touch upon some of the issues opened out:

Drawing as mapping, a post that asks questions as to the sorts of languages you might use when responding to various real life stimuli.

The frame, a post that opens out the dialogue surrounding how to frame an image. At the end of this post is a link to the Parergon by Deridda.

Thanks for the blog...

ReplyDeleteHow to pass Nebosh IGC3

Nebosh IGC Registration

IOSH MS course in Chennai

Nebosh Course in Chennai

Safety Courses in India